|

| Nancy Estes Row (Courtesy of Ellen Apperson Brown) |

Nancy Estes was born on Greenfield plantation on October 13, 1798 and lived there virtually her entire life. She was one of six sisters and four brothers. These children grew up in relative affluence and the Estes family were numbered among Spotsylvania County's gentry. During his lifetime Richard Estes, Nancy's father, owned a farm that then consisted of 748 acres and in any given year was worked by as many as two dozen slaves.

The Estes children would have been accustomed to the presence of black slaves from birth. Field hands would have spent six days a week, from sunrise to sunset, working in tobacco, wheat, corn, clover and so on. Those with special skills would be found in the blacksmith shop, the carpenter shop, the shoe shop or the weaving house. The house servants saw to the needs of the family--cooking, cleaning, caring for their clothes and the endless chores performed in a day before modern conveniences.

Family tradition has it that the Esteses were a stern, dignified people and one look at my great great grandmother's photograph above certainly tends to confirm that. The house servants were supposedly imbued with the same sense of dignity and felt empowered to reprove their young masters and mistresses when they might stray from the straight and narrow. The death of any of these slaves was occasion for mourning at Greenfield, and as was the custom the deceased would lie in the parlor before being buried in the cemetery set aside for the slaves.

But there was never doubt in anyone's mind at Greenfield as to the nature of the relationship between master and enslaved. As we have already seen, slave auctions could be held at any time and for any reason sufficient to Richard Estes. Families could be separated forever when the auctioneer's gavel came banging down.

Nancy Estes married her second cousin, Absalom Row of Orange County, on November 2, 1825. Over the next eighteen years Nancy would bear five children, four of whom would survive to adulthood. Nancy's four brothers looked westward to seek their destinies and by the late 1830s they had all moved to either Missouri or Kentucky. Their longing to move away from Spotsylvania made it possible for Absalom to buy Greenfield from the estate of Richard Estes after his death in 1832.

For the twenty three years he lived at Greenfield Absalom typically would employ twenty five slaves in any given year. These men, women and children performed the same tasks as those who had worked for Richard Estes. In addition, they would be hired out to neighbors, sent to work in the gold mines or otherwise utilized as circumstances dictated.

Absalom Row died in 1855. In his will he named Nancy as the executrix of his estate. After his will was proved in April 1856 Nancy Row became the mistress of Greenfield, now grown to 889 acres. She also became the manager and caretaker of twenty five slaves (Absalom intended his estate to ultimately go to his children; he "loaned" it to Nancy for as long as she lived). The names of those enslaved black people are listed on last week's post. In 1856 Nancy was fortunate to still have the services of overseer James H. Brock, who also lived at Greenfield.

Absalom's will empowered Nancy to give to her married children any of the family's property, including slaves, as long as a proper valuation was made. The intention was that the values of these slaves would be deducted from the individual share of each heir who had received them in the final accounting of the estate.

|

| Slaves given to Martha Row Williams |

In February 1851 Absalom Row gave to his daughter and son in law, Martha and James T. Williams, two black children--twelve year old John and eleven year old Ellen. In June 1857 Nancy gave them nine year old Patsy, whose name appears on the inventory of Absalom's estate.

|

| From Greenfield's ledgers |

This page from one of Greenfield's ledger books tells us how slaves might be utilized by the Rows to make money when not working on their farm. On February 7, 1855 Absalom noted that he had hired out Addison and William to work at the gold mine at Grindstone Hill in Spotsylvania for fifteen dollars per month. In June 1859 Nancy sent Thornton to work in the blacksmith shop of J.W. Landrum for nine dollars per month.

|

| 1860 slave census |

The 1860 schedule of slave inhabitants living in St. George's Parish in Spotsylvania County shows that Nancy Row owned twenty three slaves. Nameless here, they are listed by age in descending order. Otherwise we know only their sex and race ( all of Nancy's slaves were deemed black. Mulattoes were designated with the letter 'M'.) The oldest of these people was a fifty year old man; the youngest a six month old girl. Half of Nancy's slaves were children under the age of thirteen. One of these children was designated to run errands for Nancy's sister Polly Carter, who lived at Greenfield after leaving her husband about 1838.

|

| Slaves given to Bettie Rawlings |

On November 1, 1860 Nancy's youngest daughter Bettie married Zachary Herndon Rawlings at Greenfield. The day after Christmas that year Nancy gave them a bed and other furniture and two black children, sixteen year old Adaline and fourteen year old David. The ever conscientious Nancy Row noted the valuations of this property given from the estate of her late husband, as required by his will. Again, the intent was to have this on record in order that these amounts could be deducted from Bettie's share of the Row legacy after her mother's death.

Virginia seceded from the Union and joined the Confederacy in April 1861. Nancy's seventeen year old son George returned home to Greenfield from Albemarle County, where he had been attending the Locust Grove Academy for Boys. George enlisted in Company E of the Ninth Virginia Cavalry. Nancy selected one of the slaves closest in age to George and provided them with the two best horses at Greenfield. And so young George and his servant rode off to war.

Except for the not wholly unexpected rout of the Yankees at Manassas, much of 1861 passed without the scale of deprivation and bloodletting that would come in the following years. Most Virginians remained convinced that the independence of the Confederate States would not be successfully challenged by the North.

Change in the Row's world would come early and often beginning in 1862. Forty seven year old James H. Brock, the overseer at Greenfield since 1849, resigned his position in March 1862 and was replaced by John W. Hopkins. I do not know why Brock would have left at such a crucial time. He had been both a friend and employee of the Rows and lived at Greenfield. Did he see the handwriting on the wall? Was there a change in the attitude of the slaves that made him uncomfortable? Regardless, it is likely what happened next would have occurred no matter who was overseer at Greenfield.

|

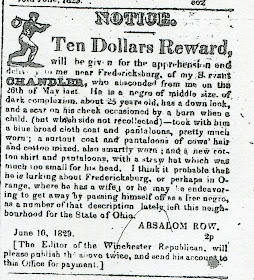

| Runaway slave notice 1862 |

|

| List of Nancy Row's runaway slaves |

During the summer of 1862 as many as ten thousand slaves escaped their bondage in Spotsylvania and surrounding counties and made their way to Union camps north of the Rappahannock River. Included in this exodus were twenty slaves belonging to Nancy Row. These were primarily the Upsher and Taliaferro families [A personal note here. Among my classmates at Spotsylvania High School were the Upshurs and the Tollivers, a variant of Taliaferro. We sat in class together with no idea of our shared past]. Thornton, who had been hired out to Mr. Landrum in 1859, also made good his escape.

|

| Notice to Judicial Officers |

|

| From Nancy Row's 1863 affidavit |

|

| Transcription of Nancy Row's affidavit |

|

| Transcription of Nancy Row's affidavit |

|

| Transcription of Nancy Row's affidavit |

The sudden disappearance of most of her slaves was a devastating economic blow to my great great grandmother. The value of the slaves comprised over half of the net worth of her late husband's estate. In October 1861 acting Secretary of State for the Confederacy, William Browne, issued a "Notice to Judicial Officers." In this document he provided guidelines to be followed by officers of the court in taking affidavits from slave owners who had lost their property by action of the enemy, meaning the Union army. These former owners hoped to thereby lay the groundwork to someday get compensation for their loss.

By the autumn of 1862 Nancy's son in law, Zachary H. Rawlings, had mustered out of Company A, Thirtieth Virginia Infantry due to illness or wounds. He assisted Nancy in the preparation of an affidavit which detailed her economic loss. Acting as her attorney, Zachary filed this affidavit with the Corporation Court of Fredericksburg on January 22, 1863. The list of runaways in this document submitted to the court contains the name of fifteen individuals, whereas the notice written in the hand of Nancy Row showed twenty. This leads me to believe that five of those slaves returned to Greenfield. Whether they did so voluntarily or not I cannot say with certainty. One of those who returned was William Upsher, whose name appears in family letters later in the war. The valuations of the slaves in the affidavit reflect the inflation of Confederate currency. Former overseers James H. Brock and John W. Hopkins attested to Nancy's legal ownership of the slaves mentioned and the validity of the values assigned to them. For Nancy Row and the thousands of other Southerners who filed similar petitions this was an exercise in futility. No compensation would be forthcoming. Nancy's affidavit ends abruptly, which tells me that at least one page is missing from the archive.

|

| Greenfield slaves hired in 1863 |

After the loss of most of Nancy Row's slaves, agricultural work at Greenfield came to a virtual halt. The handful that remained with her would be used for other duties or would be hired out to others. In the passage from one of Greenfield's ledgers shown above, we see the entry: "Limus commenced working at Kube's [Bernhard Kube was a neighbor of the Rows] Dec 17 1863 finished Dec 23 63." Just beneath that is the entry: "Nancy Row Dr Jas. Rawlings [father of Zachary H. Rawlings] for 1 hand at work 6 days." And beneath that is an entry not about the slaves but interesting to me for another reason. "Col. E. Row [younger brother of Absalom and former sheriff of Orange County] Dec 22 to 1 hind quarter beef bought weight (80 lb) at 50 cts $40. Rec'd payment Nancy Row. By son." This last entry is significant because in December 1863 Nancy's son George Row was listed as absent without leave from the 6th Cavalry, for which he would be court martialed and reduced in rank. He had come home to help his mother and sister.

|

| Detail of 1863 map of Spotsylvania |

On May 2, 1863 twenty six thousand Confederate soldiers commanded by Stonewall Jackson made their way through Greenfield plantation in their famous flank march that culminated in the destruction of the right wing of the Union army during the battle of Chancellorsville. These soldiers in gray came through the family farm on what is now Jackson Trail West. In the 1863 map shown above, Greenfield can be seen in the lower center of the image and is indicated as "Mrs. Rowe." While the outcome of the battle was favorable to the southern cause, having the war come literally to their doorstep was an unnerving experience for the Rows. In early 1864 their unease only increased as the Union army massed just north of the Rapidan River for another thrust into Spotsylvania County. Zachary Rawlings' younger brother Benjamin, captain of Company D of the Thirtieth Virginia Infantry, had been captured during the Mine Run campaign in November 1863. He would spend almost a year in a series of Federal prisons before being exchanged and rejoining his regiment. While a prisoner at Point Lookout, Maryland Benjamin wrote a letter to his mother dated March 1, 1864. In it he somberly warned her: "You should be careful not to allow yourselves to become in contact with the Yankee army on its next advance. Save what you can. Fall back with the negroes" [Byrd Tribble, Benjamin Cason Rawlings: First Virginian for the South, p.90. Butternut and Blue, 1995].

Whether or not the Rows and Rawlings required this extra bit of encouragement to leave Spotsylvania is not known. We do know, however, that before the battle of the Wilderness commenced in May 1864 Greenfield was abandoned. Nancy, her unmarried daughter Nannie, Bettie and Zachary Rawlings and their daughter Estelle and Zachary's parents James and Anna Rawlings packed up what belongings they could into carts and fled to the crossroads village of Hadensville in Goochland County. Here they would spend much of their time in comparative safety for the duration of the war.

|

| George Row to Nannie January 1865 |

On January 29, 1865 my great grandfather, George Washington Estes Row, wrote a letter to his sister Nannie in Hadensville. He describes the pitiable condition of the men and horses of his regiment after Rosser's raid on Beverly, West Virginia. George had just rejoined his company after staying several days in Spotsylvania. While there he hired out Limus to a Mr. Childs, who apparently had rented Greenfield in the absence of the Rows.

|

| Martha Williams to Nancy and Nannie Row 1865 |

In the last year of the Civil War a routine emerged whereby Nancy Row and her extended family were able to sustain themselves. Utilizing the few slaves remaining to them, the Rows were able to move goods among three locations as they were needed--Greenfield, Hadensville and Richmond, home of her daughter and son in law Martha and James T. Williams. James was a partner in the auction house and wholesale grocery concern of Tardy & Williams located at 13th and Cary Streets. Items he obtained through the blockade that were sold through his business--cotton, wool, saltpeter and Jamaica ginger, for example--as well as Richmond newspapers would be sent to Hadensville or Greenfield. Nancy Row would dye the wool and make it into uniform trousers for her son George. Whatever foodstuffs from Greenfield could be shared with relatives were put on carts and driven by a slave to one of the other locations. In a letter dated March 6, 1865 Martha Williams wrote to her mother and sister: "I hired William out at 30 dollars in April and 40 dollars a month til about the middle or first of October when all the men were sent to the trenches. After that we had him here a month making shoes and at the same hire..."

|

| Nannie Row to her mother March 1865 |

Shortly after Martha wrote her letter, Nannie wrote to her mother from Greenfield: "William arrived here yesterday morning to breakfast very unexpectedly to us. I read the letter he brought, also the almanac and some cakes and candy Sister sent, the cakes very much broken in William's carpet bag so you will have but poor eating. You will see by Sister's letter that it will not do to send William back to Richmond--although he has a note from the man who hired him last year wishing to hire him again, he will go in the reserve force and William will be left idle to get into all sorts of mischief and land in the fortifications." At the end of the letter Nannie writes that she has a possible solution to keep William employed. "Dr. James said there is a man in his neighborhood who might hire William, but he did not say what his name was as the Dr. offered to serve us in any way. I think you had better write him a note and sent William over there, he lives in the bend of the river near Loch Lomond post office." This letter was taken to Nancy Row by William in one of his last duties as an enslaved man. In less than a month the war, and the institution of slavery, would be history.