|

| Joseph Patrick Henry Crismond |

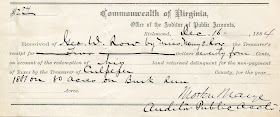

The sudden death of George W.E. Row in 1883 brought upon his widow, my great grandmother Lizzie Houston Row, a host of unexpected challenges. First among these was qualifying as administratrix of his estate and spending the next several years closing out his affairs. During this time she had frequent correspondence with the clerk of court for Spotsylvania, JPH Crismond, an example of which is shown below:

|

| Crismond receipt 1885 |

Near the end of his career as clerk Lizzie had occasion once again to have legal business with Crismond. Below is a check dated 1902 made payable to Rev. JPH Crismond, which he endorsed to Lee J. Graves as attorney for W.J. Brightwell:

|

| Check to Crismond 1902 |

|

| Check to Crismond 1902 (reverse) |

All of the papers exchanged between my great grandmother and Crismond appear in good order and I have no reason to think that there was anything amiss in her dealings with him. I include these examples only to show that over the years Crismond had some impact on Lizzie's life, as he did did on the lives of virtually all the citizens of Spotsylvania county.

|

| JPH Crismond at Spotsylvania Courthouse c. 1890 |

Joseph Patrick Henry Crismond was born in 1846 to John and Jane Crismond. In 1864 he enlisted in the 36th Battalion of Virginia cavalry and was wounded at the battle of Woodstock. He is said to have later enlisted in the Ninth Virginia Cavalry, but I have been unable to find any official record that confirms that.

After the war Crismond returned to Spotsylvania and married Sallie Carnohan in 1866. Crismond and Sallie had two children. Dora, born in 1867, married Dr. William A. Harris (physician to my Row ancestors), who was the son of Spotsylvania sheriff T.A. Harris. The Crismond's son, Arthur Hancock, was born in 1869. The censuses for the years 1870 and 1880 show JPH Crismond making his living as a farmer.

|

| Dr. William A. Harris |

At some point Crismond became active in politics and was elected Spotsylvania clerk of court in 1881, a position he would hold for the next 22 years. He was also a Methodist deacon, active in Zion Methodist Church, and an ordained minister. Over the years he would officiate at many weddings and funerals.

|

| Spotsylvania Courthouse c. 1890 |

The photograph above shows JPH Crismond (17) standing next to his son Arthur (15). His future son in law William A. Harris (5) is dressed in white at left. William's father, Thomas Addison Harris (13) is standing near the center of the group.

|

| Spotsylvania Courthouse (left) early 1880s |

The years rolled peacefully along. Crismond was popular and respected both as minister and as clerk of court. In April 1899 a committee was appointed by Judge R.E. Waller to examine the clerk's office and they reported on "the condition of the papers in the office and the manner in which they are kept...found everything in admirable condition." This glowing endorsement of Crismond's work was signed by attorneys St. George R. Fitzhugh and James L. Powell.

|

| Horace F. Crismond |

Horace Crismond was the younger brother of JPH. He was a well respected merchant in Fredericksburg and a partner with Marion G. Willis in the firm of Willis & Crismond, grocers and commission merchants with whom George W.E. Row did much business. Shortly after Horace died on January 17, 1903 things began to go terribly wrong in the world of JPH Crismond.

By July 1903 there had been whisperings of irregularities in the accounts kept by the Spotsylvania clerk's office. On July 7 Crismond made a will, leaving his property to his wife. He then drove to Fredericksburg. He left his horse and buggy at the livery stable and notified his wife to send for it. He had also left a note for his wife informing her that he was leaving for good, and she would never see him again. He then presumably took a northbound train. "It is alleged that his accounts are a little tangled," the

Virginia Citizen helpfully reported. "He has been believed partially demented since the death of his brother, Hon. Horace F. Crismond of Fredericksburg, some months ago."

Arthur H. Crismond, who worked as deputy clerk of court for his father, announced that he would not be a candidate to fill the vacancy left by his missing father, but that he would step in on a temporary basis until the matter was cleared up.

|

| Richmond Times Dispatch 22 July 1903 |

On July 22 it was reported that a body retrieved from the North (Hudson) River in New York City was presumed to be that of the missing Spotsylvania Clerk. Arthur H. Crismond, Dr. W.A. Harris and Horace F. Crismond, Jr. traveled to New York to make a definitive identification.

|

| Richmond Times Dispatch 24 July 1903 |

This puzzling development added some complication to an already baffling case. If that was not Joseph Patrick Henry Crismond in that New York morgue, then where was he? The mystery was revealed a couple of weeks later, when Judge Waller received a letter postmarked in Mexico.

It was from Crismond. In this letter he tendered his resignation as clerk and asked that his son Arthur be appointed to the position. Waller did in fact appoint A.H. Crismond to fill the vacancy left by his father's departure, pending and investigation of the affairs of his office.

On August 14, 1903 it was reported that Judge Waller appointed a committee to investigate what exactly had been going on the clerk's office and to try to ascertain whether any crimes had been committed. The committee was comprised of Judge A.T. Embrey, E.H. DeJarnette, Jr. and Henry W. Holladay.

These men set to work with purpose and conviction. They notified Judge Waller that they would be prepared to present their report on September 7. Rumors abounded that JPH Crismond would be in court that day to confront his fate.

The report was delivered as scheduled, but Crismond was a no show. The following day Judge Waller appointed Sheriff T. A. Harris as acting clerk of court and J.P. Turnley to succeed him as sheriff. County treasurer W.G. Willard resigned.

|

| Thomas Addison Harris |

On November 3 Arthur Crismond announced that he was prepared to pay the shortages discovered in the clerk's accounts. The grand jury indicted his father on eight counts, the most serious of which were embezzlement and forgery.

Four months after his abrupt and bizarre disapperance, JPH Crismond had yet to appear in Spotsylvania.

On November 8, 1903 the

Richmond Times Dispatch reported that Arthur Crismond made restitution as follows: $3,746.74 due to the state of Virginia; $203.76 due to the county of Spotsylvania; $484.63 for the cost of the investigation; and $27.54 for witness attendance before the investigating committee.

|

| Restitution made in full |

JPH Crismond returned to his home in Spotsylvania on November 23, 1903.

In December, as the date for Crismond's trial in county court approached, there was yet another interesting twist in a drama with no shortage of them. A petition signed by 67 citizens was presented to Judge Waller asking that he recuse himself from the case. Waller fined Fredericksburg Commonwealth's Attorney Charles D. Foster for contempt of court for his supposed connection to the petition. Waller also promised similar action would be in store for the signers themselves. Foster resigned as prosecutor in the case the following day. Lee J. Graves was appointed as his replacement. Within another week contempt charges against the signers of the petition were dismissed.

After all this legal flapdoodle the trial at last got underway on January 5, 1904. St. George R. Fitzhugh was the lead attorney for Crismond. Day one did not progress far before prosecutor Lee J. Graves fell ill. A couple of weeks passed during which little happened except for the courtroom histrionics of Fitzhugh and temporary prosecutor Gordon. Finally E.H. DeJarnette was selected to finish prosecuting the case.

On January 20 the Fredericksburg

Free Lance reported that Fitzhugh made the point that because there was not intent on Crismond's part to defraud the state then the charge of embezzlement could not be proven. While Crismond's negligence was a serious matter, he allowed, it was not a felony. After receiving their instructions on the embezzling charge, the jury retired to consider the evidence. Within five minutes the jury returned with a verdict of not guilty. A spontaneous demonstration of approval came from the spectators and the judge had to gavel the proceedings to order.

Feelings ran high during the course of the trial. One day a Mr. Waite came to the clerk's office and asked Sheriff Turnley for a list of the jurors' names. Turnley refused to comply and the two men came to blows and had to be separated by clerk T.A. Harris.

In fact, Crismond would be found not guilty of all the charges against him, save one. The charge of forgery would be tried in circuit court by Judge J.E. Mason.

In May 1904, before this case came to trial, the

Richmond Times Dispatch reported a bit of Methodist news that showed that Crismond enjoyed the support of much of the community: "JPH Crismond, local deacon of the Spotsylvania circuit, made his report to the conference and on motion his character passed."

And finally, on June 9, 1904 the prosecution announced that they would now drop the forgery case pending against Crismond. After almost a year of tumult Crismond had escaped legal consequences for what were very serious charges.

Still, controversy continued to cling to him.

On October 5, 1904 JPH Crismond was indicted for attempting to steal three pairs of shoes from the Spotsylvania store of Harris & Frazier. He was carrying out two pairs of shoes and wearing one pair with the price tag still affixed. The

Free Lance reported that "The friends of Crismond say his mind must be deranged as there was no reason for committing the act, as he has ample means..." The next day the charge was dismissed when the store's owners declined to prosecute.

The end result of all of this, at least in the short term, was the end of Crismond's viability in Democratic politics. So he switched his allegiance to the Republican party. He served on the boards of several organizations and continued to hold services at weddings and funerals. But there would be one more turn of the wheel as far as Crismond's public notoriety went and this would play out in the pages of the

Free Lance in late 1910.

On September 22 of that year the county's Republicans assembled to elect officers. J.P. Turnley nominated attorney Samuel P. Powell to be chairman. At this Crismond leaped up and indignantly said that Powell had already pledged his support for R.C. Blaydes for that post and accused Powell of "gross inconsistency." Blaydes was elected chairman. Samuel P. Powell was elected secretary "without opposition in place of Mr. Crismond, who said that he would not have the place any longer."

A month later the

Free Lance published an open letter by Powell which accused Crismond of misstating the events of the meeting. In like manner JPH replied on November 1, insisting that Powell had indeed pledged his support for Blaydes and accused him of being a sore loser.

Powell was unwilling to let the matter drop. His rejoinder, published on November 10, 1910, upped the ante in their escalating war of words. He claimed that Blaydes "willfully and deliberately misunderstood me." Then Powell reached for the jugular by dredging up the events of 1903: "[Crismond] was forced [to flee] by his fear of a felon's cell in the convict ward of the penitentiary when it became known that he had diverted many thousands of dollars of the State's money...to his own private purposes." And then this: "If there is a man I abhor it is the oily tongued hypocrite who pretends to be my friend."

Crismond's retort of November 26 begins: "He who the gods would destroy they first make mad." He is just getting warmed up. "Powell was so full of bitter venom that he had neither the fairness nor the honor to give the truth its due...My going away in 1903 had nothing to do with the clerk's office, and God and one man only besides myself knew what my mission was." He then says that before the trial he was approached by Powell's father (who signed the glowing report of 1899) and recommended Samuel as defense attorney for Crismond, who said he declined the offer.

The testy--and often bombastic--exchange between these two reached a crescendo before Christmas 1910. In a withering philippic dated December 22, Powell let loose the remaining arrows in his quiver. He refutes the claim that his father had tried to arrange the defense attorney job by producing a letter he claims to show that, in fact, Crismond had approached the senior Powell to serve as his counsel and James L. Powell declined. Powell then returns to the notorious trial of 1904: "By some technical miscarriage of justice he was not sent to the penitentiary for his manifold crimes." He then goes on to insinuate that Crismond dumped the fee books and other records into the Mississippi River during his flight to Mexico. Not content to stop there, Powell accuses JPH and R.C. Blaydes of soliciting a bribe from B. Wiglesworth in order that he might keep the post office in his store.. He characterizes them as "hypocrites, blackmailers, grafters, bribe takers, falsifiers and conspirators."

My, my.

To my knowledge JPH Crismond never publicly explained his behavior of 1903.