|

| George Washington Estes Row |

April 1883...

The last eight years had been good ones for George Row. With the ardor of a younger man he had successfully courted Lizzie Houston of Rockbridge County and had married her in December 1875 (George was eleven years older than his bride). He brought her back to Greenfield, the old Row plantation in Spotsylvania, and there they lived with George's unmarried sister Nan for the next four years. George's and Lizzie's first two children were born at Greenfield: Houston in 1877 and Mabel in 1879. In 1880 George built a house for his growing family at Sunshine, the section of Greenfield deeded to him by his mother in 1869. The first child born there was Robert Alexander Row in 1881. (Little Robert died that same year. Lizzie Row cut a lock of his blond hair and sewed it to a piece of paper and put it in her trunk. It is still there.) The youngest child, Horace--my grandfather--was born in July 1882.

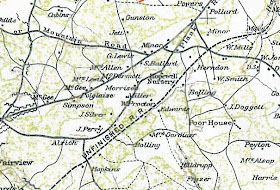

During these years he lived with Lizzie, George also prospered in his business affairs. George was successfully farming both Greenfield and Sunshine. He built a saw mill and shook factory on Joseph Talley's farm near Finchville. His customers included both versions of the railroad that extended from Fredericksburg to Orange; the many merchants in Fredericksburg with whom he did business; and a good number of friends and neighbors in Spotsylvania and Orange. The ledger books of his businesses include the names of many local citizens who were noteworthy in those days. In these enterprises George employed dozens of workers, most of them freedmen.

George Row was a minor participant in local Democratic party politics. He had worked with X.X. Chartters in establishing the Wilderness Grange. He was a member of the Masonic lodge in Fredericksburg.

But it had not always been as good as this. There were dark times, as well, as there are for us all. His father died when George was twelve. His education was cut short at age seventeen when he enlisted in the Confederate service, spending four years in the saddle first with the Ninth Cavalry and then the Sixth Cavalry. While he survived the war unscarred and uncaptured, he had witnessed death and devastation on a scale difficult for us to imagine today. His emotional and mental resilience was sorely tested a second time during the period from November 1871 to January 1873 when his first wife Annie, his daughter and his mother died.

But by now, in early April 1883, George had been able to set aside the melancholy that followed him for years and he was hitting his stride as an entrepreneur and as a husband and father. You could not fault him if he were to look into the far blue distance and see more good fortune awaiting him in the years to come.

But in that first week of April something was going wrong. Terribly wrong. George had fallen ill and instead of improving his condition rapidly declined. The doctors said it was typhoid pneumonia. George took to his bed and remained there for the short time remaining to him.

|

| Sunshine, 1957 |

This was the house that George W.E. Row built in 1880. Come, look:

This house, built on the farm he named Sunshine, stood for over one hundred years. He had added front and back sections to an existing log structure, the door to which is seen on the right of the house. The front door faced north, and upon entering you came into the parlor with a fireplace on the east wall. I remember a painting on the north wall depicting a doctor attending a sick child. There was a framed piece that read "The Lord will provide." On the right, as you passed through the parlor, was the beaded board wall that enclosed the steep, narrow steps that led to the garret where the children slept. Just before you reached the log section of the house was the bedroom in which George Row now lay dying. You see the bedroom window on the right side of the house. In this same room my mother would be born forty five years later. The rear section of the house included the kitchen and another attic space.

Perhaps because of his experiences during the Civil War, or maybe it was just his nature, George always had a certain ambivalence about religion and he never joined a church. This would be a source of worry to his sisters. But for some reason during the last months of his life he decided to teach a Bible study class for the men's Sunday school at Shady Grove Methodist Church. In appreciation the men of the church gave him a mustache cup for Christmas in 1882.

|

| George Row's notes for Bible study class |

|

| Mustache cup given to George Row |

Two doctors attended George during his sickness. They did what they could for him, which was not much, and they did their best to calm Lizzie's fears. Doctors Addison Lewis Durrett and Thomas W. Finney both served in the 9th Cavalry with my great grandfather. In 1881 Dr. Finney had been unable to save Robert Row. In 1872 Dr. Finney, together with Dr. John D. Pulliam, also unsuccessfully treated George's mother Nancy during her final crisis. (Dr. Pulliam was a son of Richard Pulliam, who lived next to Greenfield. The 1860 census shows that Dr. Thomas W. Finney was living in the Pulliam household. John Pulliam was a medical student that year).

|

| Receipt given by Thomas Finney to Lizzie Row |

A year after her husband's death, Lizzie Row wrote a letter--intended to be read by her children when they were older--in which she describes this time:

During his sickness before he was unconscious we were alone. I asked if he still loved me and he said "Yes" and put his arms around my neck and said "I love you the house full, the barn full and all out of doors." This is what he used to teach you all to tell him. Your father was not a church member but I think a Christian. His motto was "Do justice, love mercy and walk humbly with thy God." He was not sick quite two weeks, was not conscious when he died, but breathed quietly. Mabel was at Greenfield, Horace asleep and Houston by me on the bedside. I hope you will all meet him "on that beautiful shore..."

George Row, age thirty nine, died in the early hours of April 18, 1883. Great grandmother Lizzie took her scissors in hand and cut three locks of hair "from his dear forehead" and sewed them to sheets of his business stationery.

Lizzie engaged the services of Frederickburg undertaker William Nossett, who was in business with his son George. My great grandfather's burial case and box cost fourteen dollars and seventy five cents.

|

| The Free Lance 25 January 1889 |

Two dollars was paid to have the grave dug at the family burying ground at Greenfield. Lizzie Row wore this mourning cloak to the funeral.

|

| Mourning cloak of Lizzie Row |

Shown below are three notices of George Row's death published in the Fredericksburg newspapers. The first two are pasted in the Row family Bible.

|

| Obituaries of George Row |

| |

| Obituary of George Row |

...Mabel your father loved you dearly, and I thought your little heart would break when we came back from the burial. You went through the house calling "Father" and asked "Why didn't God let Father stay until tomorrow when I come. I wanted to see him so bad." Dear children you are all bright and happy now. You don't know your loss while I am so sad and lonely. Dear "little Hossie" [Horace] as Father used to call you can't remember sitting on my lap and holding Father's hand while he was sick in bed.

|

| George T. Downing's receipt to Lizzie Row |

For the next several years Lizzie struggled to raise her children, manage Sunshine and settle the accounts of her late husband's estate. Six years after his death she was at last able to hire Fredericksburg stone cutter and marble salesman George Titus Downing to craft a headstone for George. (Photo by Margie McCowan)