| ||

| Horace Row |

Just to be clear, I do not for a moment believe any of this was the cow's fault.

In fact, in all likelihood it was probably one of those misunderstandings that can arise during a transaction between parties acting in good faith. I would like to believe that there was no conscious intent to defraud or hoodoo a neighbor and fellow dairy farmer.

That said, this whole affair could have been handled with a little more tact and subtlety by Mr. Row, about whom I had more to say here. And in that case the rupture in whatever friendly relations that existed beforehand could have been avoided.

|

| M.W. Thorburn, 1890s. Photo courtesy of Rich Morrison |

In my last two posts I introduced Mungo William Thorburn, pictured above with a woman who was likely Mary Douglas, his second wife. Born in Scotland, Thorburn arrived in Spotsylvania by 1900 with two daughters and having lost a son and his first two wives. In 1904 he married Abbie Morrison and with her had three sons. Everything that I have read about M.W. Thorburn leaves the impression that he was a highly capable man of sterling character--hard working, pious and civic minded. He was noted for having spent fifteen years reclaiming boggy land on his farm and adding that acreage to his crop rotation. He served on the board of public roads in Spotsylvania and was a crucial player in the long term success of the Fredericksburg & Wilderness Telephone Company. Thorburn was a devoted supporter of Tabernacle Methodist Church. He was highly regarded by those who knew him.

Because I know more about him, the portrait of my grandfather Horace Row is a bit more complicated. He was born in 1882 on Sunshine farm, the section of old Greenfield plantation that has remained in my family since 1795. Horace lived at Sunshine his entire life. His father died when Horace was nine months old, and he became the man of the house at age seventeen when his older brother Houston died in 1899. Horace Row was a successful farmer, an astute manager of his money and the father of five children.

He also had a prickly personality and had an unfortunate talent for alienating people. And he was an undisguised foe of Prohibition.

|

| M.W. Thorburn's first note to Horace Row |

In the summer of 1927 Mungo Thorburn wrote a note to Horace, expressing an interest in buying one of his milk cows. The tone of the letter hints at a friendly, if somewhat formal acquaintance: Mr. Rowe--Dear Friend--I will be up to look at the cows as soon as I can. I'm filling my silos today and part of tomorrow. Yours truly, M.W. Thorburn.

By October 3 it is apparent that things have not gone according to Mr. Thorburn's expectations. Since we were not present when the cow changed hands, it is not possible to know what was said by my grandfather that day. But the letter that M.W. Thorburn next wrote to Horace leaves no doubt that he feels that he was not dealt with fairly.

|

| M.W. Thorburn's letter to Horace Row |

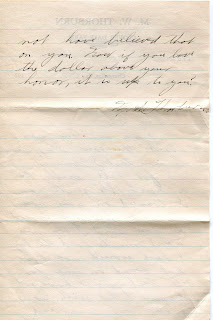

| ||

| M.W. Thorburn's letter to Horace Row, p. 1 |

|

| M.W. Thorburn's letter to Horace Row p. 2 |

Mr. Rowe--

Dear Sir,

I am writing you about this cow. I explained to you that I wanted her for fall milk. As a honorable gentleman I trusted on you, now the cow has not proved as you said. Then you want me to hold the bag. I would not have that brand on me for the best cow I have got. I have talked with some of the best men, and they said they would not have believed that on you. Now if you love the dollar more than your honor, it is up to you?

M.W. Thorburn

Horace's reply, preserved in a draft of a letter intended for Thorburn, makes his point with a minimum of neighborly diplomacy. I am sorry to say that this is the only example of my grandfather's writing as an adult that survives in the known record. And I certainly wish it depicted him in a more flattering light:

In reply to your letter of yesterday will say that you bought the cow on your own judgment and your three sons and son in law. You all felt her good and milked her, looked her over three times. When I did not care to sell I told you the date I took her away on and by her look and actions looked for her to run in Aug., but I did not have ex ray eye of corse and you said of corse not. I have seen some good men about it and they were surprised at you not expecting such a good offer as I made you and the offer is still open beside I have bought a lot of cows and calf & horses in my life and I found that they some times do not turn out as I expected them to but I was man enough not to squeal but to take my medisson. If you will please show this letter to the men you talked to they will see that I am strait in my dealings as any man.

=

You deliver her to me in good shape and take the other on back at your expense.

In October 1939 Horace and my uncle George drove the farm truck to an orchard in Sperryville. That day my grandfather died of a heart attack while picking apples. In the weeks to come my grandmother received dozens of letters of condolence from friends, relatives, schools and churches. It will probably surprise no one that there was not one from M.W. Thorburn.

My grandmother pasted her husband's obituary in the old family Bible. Whether or not she chose this page intentionally I cannot say. It could be just coincidence and not a subtle jab from her.

But sometimes I wonder.

|

| Obituary of Horace Row |

.jpg)