|

| La Vista, 1858 (Encyclopedia of Virginia) |

Standing now for almost 165 years on what is now known as Guinea Station Road in eastern Spotsylvania County, La Vista is a living symbol of the Boulware family, who built it and owned it for the first 47 years of its existence. The story of La Vista is in no small measure emblematic of its time and place. Its history includes the themes of antebellum wealth and post-war calamity, slavery and reconstruction . My thanks go to Michele Schiesser, whose generosity and assistance made this article possible.

|

| Gray Boulware |

|

| Harriet Terrell Boulware |

(The original portraits of Gray and Harriet Boulware are owned by Bob Lang, and were photographed by Robert A. Martin)

The story of La Vista begins with the man who built it. Gray Boulware (pronounced "Bowler") was born into a large and well-to-do family in Caroline County on May 15, 1792. Little is known of Gray's early life. In Marshall Wingfield's A History of Caroline County, Gray's name appears on the 1813 muster roll of Captain William F. Gray's Company, 30th Virginia Infantry and on the 1814 muster roll of the 16th Regiment commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Aylett Waller. It is not known whether Gray saw any fighting during the War of 1812.

|

| Map detail of Caroline County, 1863 (Fold3.com) |

Gray married Susanna Miller in 1818. She died shortly thereafter. In 1820 or 1821, Gray bought Arcadia, a large farm in Caroline County situated between Bowling Green and Port Royal (and now part of Fort A.P. Hill). In the map detail above, Arcadia is noted as "Bowler" near the bottom of the image, just west of the The Trap, a well-known tavern owned at that time by Martha Carter. Gray married his second wife, Harriet Terrell, on January 2, 1821. They made Arcadia their home, where they had six children together between 1821 and 1828. The house at Arcadia was described as a two-story structure with two-story porches on the front and back, and had a basement and attic. It was built on a hillock of earth made by the slaves. Its foundation was made of bricks made in a kiln on the property.

|

| Liberty Baptist Church (TheChaplinKit.com) |

Gray Boulware was a devout Baptist and an important supporter of Liberty Baptist Church, which survives to this day as the post chapel at Fort A.P. Hill. Gray's oldest daughter, Judith Terrell Boulware (1821-1850) became the first wife of Liberty's minister, Reverend Richard Henry Washington Buckner, on February 29, 1848.

|

| Map detail of Spotsylvania County, 1863 |

In May 1839, Gray bought from his nephew, Lee Roy Boulware, a 1,000 acre tract in eastern Spotsylvania County along the road to Guiney's Station. This land had originally belonged to Fielding Lewis, brother-in-law of George Washington. Gray called this farm The Grove. It is likely that he farmed this land, but he did not build his second home there until 1855. The location of The Grove (which Gray's son Jack later renamed La Vista) is shown in the map detail above as "Dr. Boulware."

|

| Richmond Enquirer 6 April 1844 |

During the 1840s, Gray appeared to be active in local Democratic politics. In April 1844, his name appeared on a list of Caroline County citizens who were members of the Committee of Vigilance. These committees were politically affiliated, extra-judicial organizations that performed certain law enforcement activities beyond those usually handled by the sheriff.

|

| Alfred Jackson Boulware (Mary Campbell) |

Gray's youngest son, Alfred Jackson Boulware (called "Jack" by his friends and family) was born at Arcadia on November 3, 1828. In an era when there was no public school system in Virginia as we know it today, Jack Boulware would have been educated by private tutors or at one of the many private academies that flourished in the region at that time. Whatever form his early education took, Jack was well prepared for his years at college and medical school.

Jack first attended Columbian College in Washington, D.C., where he received his bachelor of arts degree in 1849. While a student at Columbian, Jack met John Moore McCalla, Jr., with whom he began a romantic relationship in 1848. This was the beginning of their long friendship, which lasted for the rest of Jack's life.

|

| John Moore McCalla, Jr. (Ted Goldsborough) |

Originally from Kentucky, John McCalla came to Washington, D.C. with his family some time during the 1840s. John earned his medical degree from Columbian College in 1853, and began his medical practice in the nation's capital. In 1860, John was selected to act as physician aboard the ship Star of the Union on its voyage to Liberia. The mission of this journey was to transport 383 Africans who had been rescued from the slave ship Bogota and return them to their native continent. During the Civil War, John served as a contract surgeon at three military hospitals in Washington. As an adult John had romantic relationships with both men and women, even after he married Helen Varnum Hill. John described these relationships, including the one with Jack Boulware, in his diaries. John suffered from asthma and was forced to retire from his medical practice in 1877. He died in Washington in 1897 and was buried in Rock Creek Cemetery.

After completing his studies at Columbian College, Jack Boulware returned to Arcadia. Shortly before beginning his pre-med work at the University of Virginia, Jack had a violent confrontation in downtown Richmond in the spring of 1851. Two mentions of this incident appeared in the same edition of the Richmond Enquirer.

| ||

| Richmond Enquirer 27 May 1851 |

Jack attended the University of Virginia 1851-1852, and received his medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1853. His education now completed, Dr. Boulware was ready to enter upon the next chapter of his life.

|

| Ann Trippe Slaughter (Mary Campbell) |

On November 15, 1853, Jack married Ann Trippe Slaughter at a ceremony held at her parents' home in Rappahannock County (by coincidence, Ann's sister Maria became the second wife of Reverend Richard Henry Washington Buckner that same year). Not long after they were married, Gray began to build his second home at The Grove, his property in Spotsylvania.

The house at The Grove was finished in 1855, and Gray and Harriet made this their new home. Jack and Ann joined them there. Jack's older brother, Gray, Jr. had married Millie Hudgin in 1852 and they settled at Arcadia. Millie was the daughter of Robert Hudgin, who was clerk of court in Caroline County for decades. During their years at Arcadia, Gray, Jr. and Millie had 11 children together.

Jack and Ann's first child, Harriet Gray (affectionately known as "Hattie") was born at The Grove on February 23, 1856. Their first son, John McCalla (known as "McCalla") was born May 18, 1858. Frank, the youngest was born in 1860. In the photograph of La Vista that appears at the beginning of this article, Jack Boulware, in his top hat, can be seen sitting on the porch. Standing in the doorway is a black nurse holding McCalla, and Hattie is standing in front of them. To the left of them is likely Ann Boulware. The woman on the porch at far left is unidentified. A young black boy is playing with a dog on the top step, and a black girl stands behind the railing at right. Four enslaved adults, in addition to the nurse, are carefully posed. The identity of the person peering from behind the curtain is not known.

|

| Gray Boulware (Mary Campbell) |

In 1852, Gray Boulware bought a plantation account book from the publisher of A Southern Planter, a trade journal for Virginia farmers. On January 1, 1853 the overseer of Arcadia (whose name appears to be J.A. Stephens) listed the names of the 43 slaves at Arcadia, their job descriptions and their monetary values. The two oldest persons on the list, Frank and Edmonia, are identified as foremen. Some of the other jobs listed include hog hand, plougher, field hand, house boy and cook. Nelly and Jacob, both age 9, worked as field hands.

|

| Pages from Gray Boulware's account book (Michele Schiesser) |

Gray raised prize-winning stock, which he advertised for the State Agricultural Fair in Richmond and in The Southern Planter:

| Richmond Daily Dispatch 1 October 1854 |

|

| The Southern Planter, Volume 14, 1854 |

In 1856, a Boulware relative from South Carolina visited Arcadia and was presented with a cane with an inscribed silver head which read "Gray Bowlware [sic], Bowling Green Virginia, Nov 3, 1856":

|

| Presentation cane, 1856 (Michele Schiesser) |

On January 15, 1857, just two weeks before he died, Gray Boulware wrote his last will and testament. He bequeathed Arcadia to Gray, Jr. Jack would receive The Grove. His wife Harriet was given a life estate in both of those properties. Gray's will was witnessed by Ann J. Swann and by Richard H. Garrett, whose first wife was a niece of Gray. Eight years after he witnessed Gray's will, Garrett's name would be forever linked to that of John Wilkes Booth, who was killed at his farm in April 1865.

|

| Obituary of Gray Boulware (Mary Campbell) |

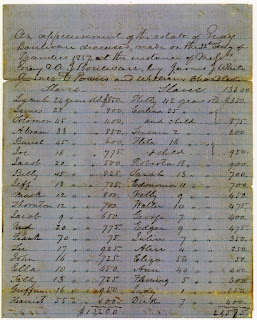

Gray's will also stipulated that the slaves at Arcadia and The Grove be equally divided between Jack and Gray, Jr. Shown below are the names of those enslaved people, 83 in all, and the monetary value assigned to each of them:

|

| Slaves of Gray Boulware, 1857 (Michele Schiesser) |

Like his father, Gray, Jr. was well known to the publishers of The Southern Journal. In the July 1860 edition, he is thanked by the editors for sending them a pig, and he is named as one of the judges of the roadster mares and fillies at the 1860 State Agricultural Fair in Richmond:

|

| The Southern Planter, July 1860 |

The 1860 census shows that Gray, Jr. had personal and real property totaling almost $66,000, making him a wealthy man for his time. He owned 47 slaves that year. In addition to his farming operations, he also owned a hotel in Bowling Green. Just before the start of the Civil War, life was good for the Boulwares of Arcadia.

The year 1860 was also a prosperous one for Jack Boulware and his family. About this time Jack changed the name of his plantation to La Vista. The census shows that six white people were living at La Vista--Jack, Ann, their three children and Jack's mother Harriet (Harriet is also shown living at Arcadia that year, which indicates that she divided her time between her two homes). Jack had a combined wealth totaling $62,000 and he owned 39 slaves. In 1860 he owned more horses than any other household in St. George's Parish--22 of them--and he raised 20,000 pounds of tobacco, also more than anyone else in the parish.

|

| Harriet Terrell Boulware (Mary Campbell) |

There is no record that I can find which provides the exact date and circumstances of Harriet's death, but it appears to have occurred about 1861.

When Virginia seceded from the Union in 1861, both Jack and Gray, Jr., supported their state's resistance to federal authority, In 1862, Gray, Jr., received a $50 bounty for his one-year enlistment in Company B of the 9th Virginia Cavalry. He also sold goods to Confederate quartermaster officers, primarily fodder. Gray, Jr. applied for a mail contract with the Confederate government. The August 27, 1864 edition of the Richmond Dispatch reported the names of 80-odd black Union soldiers (and the names of their former owners) who had been captured during the Battle of the Crater near Petersburg. Among them was John, who had once belonged to Gray Boulware, Jr.

Jack Boulware was exempted from military service, but he still aided the Confederate cause by selling tons of fodder to various quartermaster officers, and by providing the use of his wagons, with his slaves serving as teamsters. One of Jack's quartermaster receipts was signed by Elliott Muse Braxton, who in civilian life was an attorney in Fredericksburg and a former state senator.

|

| Quartermaster receipt signed by Major E.M. Braxton 4 August 1863 (Fold3.com) |

|

| Elliott Muse Braxton (Wikipedia) |

Jack's first encounter with the Union army occurred in 1862, when soldiers under General McDowell's command stole 110 barrels of corn, among other things. Further depredations took place in May 1864, when the Union army stopped to visit during their march southeast on the road to Guiney's Station. As Jack described in his application for a presidential pardon in May 1865: "I have suffered severely in property by the operations of the war. During 1862, the Federal army took from me, eighteen horses and mules, being all my working teams. The fencing on my farm has been twice destroyed, cropping in a great measure prevented throughout the war. And my household furniture and supplies of food destroyed by military violence." However, one small item was saved from the clutches of marauding United States soldiers. A silver cake tray was hidden under a hen in the chicken coop. The hen was snatched, but the cake tray escaped the notice of the hungry thief. This cake tray was at one time displayed at the National Park Service Visitor Center in Fredericksburg:

|

| Boulware cake tray (Michele Schiesser) |

The long association of the Boulware family with the legacy of General Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson began in May 1863. Two days after his left arm had been amputated due to his accidental wounding during the Battle of Chancellorsville, an ambulance carrying Jackson and a military escort slowly made its way to Fairfield, the farm of Thomas C. Chandler near Guiney's Station. As this sad entourage passed by La Vista, it is likely to have been seen by the Boulware family.

In June 1863, John McCalla was incorrectly informed by mutual friend James M. Slaughter that Jack Boulware had died of typhoid fever. While this was untrue, for the next two years John believed that his old friend was dead.

Although Jack would be more fortunate than many others during the Civil War--he had plenty of food and most of his slaves chose not to run away from La Vista--his life would be ravaged by tragedy and grief. Frank, his younger son, died (the date is unknown). On November 15, 1864, eight-year-old Hattie also died. It is said that Jack, overcome by rage and grief, tore the works out of the upright clock, screaming Hattie's name and exclaiming that the clock should keep time no more.

During the Victorian Age, spiritualism was taken seriously by many. Spiritualists were people who claimed to have the ability to communicate with the spirits of the dead. Jack Boulware managed to get a message to a spiritualist in Boston, who published a reply to him in the December 31, 1864 edition of Banner of Light:

"Hattie Boulware

Send to her father, Andrew Trippe Boulware [sic], La Vista, Spottsylvania County

I want my father to give me some one I can speak through. I died at La Vista at nine o'clock in the morning, of inflammation of the lungs and brain, on Nov 15."

At the time of the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox, there were still 28 former slaves living at La Vista, including 13 who were too young or otherwise not able to work. Jack continued to provide food and shelter for all of them. He also shared what food he had with his impoverished neighbors. In March 1865, the occupation authority of the federal army named him as commissioner to oversee which families in Spotsylvania County would be eligible to receive government rations.

On May 8, Jack applied for a presidential pardon, a necessary step to re-establish his citizenship in the United States and be able to exercise his right to vote. On that same day he took the required oath of allegiance. Gray, Jr. also took the oath of allegiance later that year.

|

| Oath of allegiance of Alfred Jackson Boulware (Fold3.com) |

On May 9, 1865, the day after Jack completed his application for a pardon, John McCalla received a message from him. It was his first communication from Jack since the start of the war, and his first confirmation that Jack was still alive. Eleven months later, Jack, Ann and McCalla booked passage on a packet and made the trip to Washington, where they visited John. Six weeks later, John made arrangements to come to La Vista in order to recuperate from a bout of illness (his wife Helen remained in Washington). He took a steam boat from to Aquia Harbor, then boarded the train from Brooke's Station to Guiney's Station. There he was met by Jack, who was driving a buggy, and eight-year-old McCalla, who was on horseback. John was shocked by the aged appearance of his old friend. The stresses of the war and the deaths of two of his children had taken their toll on Jack.

|

| Alfred Jackson Boulware, 1860s (Mary Campbell) |

On June 16, 1866, John accompanied Jack and Ann to Spotsylvania Court House in order to attend a meeting to organize the Spotsylvania Ladies' Memorial Association. The goal of the Association was to raise funds to buy land for a cemetery near the court house, to locate the remains of Confederate soldiers at the local battlefields and to transport them to the new cemetery. During the meeting, Ann was elected as first president of the Association. Afterwards, John, the Boulwares and several others, including John Horace Lacy of Ellwood, went to the springs at the nearby farm of Neil McCoull and enjoyed an afternoon picnic.

|

| Richmond Daily Dispatch 18 June 1866 |

|

| Fredericksburg Ledger 20 November 1866 |

|

| Richmond Daily Dispatch 20 June 1868 |

Two days after the meeting at the court house, John, Jack and Ann rode in an open wagon to Fairfield, the farm of Thomas Chandler, where General Jackson had died three years earlier. Chandler had offered to give the Association the bed in which Jackson had died. The intention was to make the bed available for sale in order to raise money for the cemetery and for the re-internment of the soldiers' remains. John noted in his diary that an adult daughter of Chandler (most likely Mary Chandler) gave the bed to him. When John left for Washington the next day, he gave the bed to the Boulwares and began to seek a buyer for it. In one such early effort, John approached an agent of the museum of Phineas T. Barnum, but a sale was not made. As it turned out, money from the sale of the bed was not needed, and the Boulwares retained ownership of the bed until 1900.

The losses that they incurred during the Civil War forced both Jack and Gray, Jr. to declare bankruptcy. In 1866, Jack executed a deed of trust to attorney Elliott Muse Braxton, conveying to him all of his property in trust in order to secure his debts. Jack managed to successfully navigate the bankruptcy process, and by 1869 his case was resolved.

|

| Richmond Daily Dispatch 11 August 1869 |

Gray, Jr. was not so fortunate. He was forced to sell Arcadia at public auction. The 1870 census shows his occupation as "hotel manager." Several years later, Gray and his family moved west and lived for a time in Chillicothe, Missouri before ultimately settling in Lawrence, Kansas. In 1895 Gray, Jr., was declared insane and was confined in the state asylum in Topeka, where he died three weeks later.

|

| Gray Boulware, Jr. (Mary Campbell) |

|

| Topeka State Journal 20 January 1895 |

|

| Topeka State Journal 15 February 1895 |

By 1867, Jack had become active in local politics. In August of that year he was elected as a delegate to the Conservative Party convention in Richmond.

|

| Richmond Daily Dispatch 12 December 1867 |

By late winter 1870, Jack's health began to fail. In early March he suffered a bout of jaundice and was ill for several days before he began to seemingly improve. Believing that he was out of danger, Ann made arrangements to travel to Rappahannock County to visit her mother, whom she had not seen for a year and a half. Susan Motley of Caroline County and another woman came to La Vista to stay with Jack during Ann's absence. For several days he seemed to gain strength and was in good spirits. Then he suffered from paralysis and experienced dropsy in his chest. Two days before Ann returned to La Vista, he suffered a violent hemorrhage from his nose and began to fail rapidly. Ann came home on March 18. Jack died on Sunday March 20, 1870. He was buried with his children in the family cemetery near the driveway to the house.

When Jack died, the deed of trust he had signed in 1866 was still in force. Ann moved quickly to claim her dower rights in La Vista and to secure McCalla's legacy. To that end, she petitioned the court in May 1870 to obtain legal title to the house and one-third of the land at La Vista. Attorney Thomas N. Welch was appointed as guardian ad litem to represent McCalla's legal interests in the remaining two-thirds of the land. Spotsylvania County surveyor John M. Smith was hired to survey La Vista and make a plat of Ann's dower portion of the property.

|

| Plat of La vista, 1870 |

At the time of his father's death, McCalla was away at boarding school. He was taught by a gentleman named V.H. Beasley. McCalla's education was of paramount importance to Ann, and she continued to pay for his education after her husband died.

|

| John McCalla Boulware, 1870 |

During the course of 1873, the health of 45-year-old Ann Boulware began to decline. She was treated by at least four physicians--Dr. W. Washington, Dr. Andrew M. Glassell of Caroline County, Dr. Holloway and Dr. Adolphus W. Read of Rapphahannock County. In the end, their efforts proved to be unavailing. Ann died on December 22, 1873. W.M. Jones, a laborer at La Vista, built her coffin and case for $30. She is presumed to have been buried with her husband and children in the family burying ground at La Vista.

Ann's estate was appraised at $1,449 but only $718.19 was realized at her estate sale. Ann had made no will. Her brother, Francis Long Slaughter, was appointed administrator of her estate (Francis by this time was married to Susan Motley, who had cared for Jack Boulware during his final illness). Among the many household items that had been appraised for the sale were a bird cage, a refrigerator, a bathing tub and a $150 piano. At her death, Ann still owed to the law firm of Elliott Muse Braxton and Charles Wistar Wallace the sum of $198.39 for an unpaid bond.

Since McCalla Boulware was still legally a minor, he was sent to Rappahannock County to live with his Slaughter relatives. While there, McCalla met Ada Johnston Miller, whom he married on October 15, 1879. They moved to La Vista, where they would live for the next 23 years. They had three children together--Darius Jackson (1880-1933), Gideon Brown (1884-1935) and Elizabeth Trippe (1890-1919). The 1880 census, dated June 11-12, shows McCalla and Ada (who was eight months pregnant with Darius), living at La Vista. Also living there were the Green family: adults Adelaide, the cook, and Benjamin, a laborer and children J.E.B., Robert, Lucy Annie and Carey. Soon after returning to Spotsylvania, McCalla sold his share of La Vista, keeping the tract that included the house and 338 acres.

The bed in which General Jackson had died was still being stored at La Vista. During the 1880s, Rufus B. Merchant, owner of the Virginia Star newspaper in Fredericksburg, started a fund-raising effort to erect a monument to General Jackson at the Chancellorsville battlefield. Once again, the idea of selling his death bed was proposed to help cover the cost of the monument. McCalla loaned the bed to Merchant for that purpose, and the disassembled bed remained at the Star's office for some time. Once again, sufficient funds were raised for the monument and it was not necessary to sell the bed.

|

| The Daily Star 1 March 1900 |

Once the bed came back to La Vista, it remained in McCalla's possession until 1900, when he gave it to Dr. Hunter McGuire, the surgeon who had amputated General Jackson's arm in 1863. McCalla wished for the bed to be given to the Stonewall Jackson Memorial Association, which Dr. McGuire helped to establish. The Association, in turn, gave the bed to the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond. And there it remained in storage until 1927, when it was turned over to the National Park Service. Today the bed is on display in the building where Jackson died, at the newly-renamed Stonewall Jackson death site.

|

| Southern Planter and Farmer, Volume 61, 1900 |

In addition to profitably farming at La Vista, McCalla--like his father and grandfather before him--became involved in local politics:

|

| The Daily Star 1 September 1899 |

In June 1902 McCalla sold La Vista to Charles Decatur. The Boulwares then moved to Fredericksburg, where McCalla hired A. Mason Garner to build a house on Washington Avenue across the street from Kenmore.

|

| Richmond Times 29 April 1902 |

|

| Richmond Times 16 September 1902 |

|

| The Boulware house today (Google) |

McCalla and his older son Darius started a feed and grain business on Commerce (William) Street. Over the years, they partnered in several other businesses as they changed with the times.

|

| The Free Lance 5 May 1903 |

|

| The Free Lance 14 January 1905 |

|

| The Daily Star 27 April 1917 |

|

| The Battlefield 1917 |

McCalla's other son, Brown, was one of Fredericksburg's earliest owners of an automobile and he had business plans for its use:

|

| The Daily Star 15 September 1909 |

Like his father 55 years earlier, McCalla experienced the anguish of losing his only daughter. Elizabeth was among the many who lost their lives during the influenza epidemic:

|

| The Daily Star 15 February 1919 |

John McCalla Boulware died of heart disease on April 24, 1920. His death was front page news. McCalla is buried in the Fredericksburg City Cemetery:

|

| The Daily Star 26 April 1920 |

|

| John McCalla Boulware (Findagrave) |

After McCalla sold it in 1902, La Vista changed hands many times in the years that followed. During the 1930s and 1940s modern conveniences such as electricity, indoor plumbing and central heating were added to La Vista. At about that same time, the Boulware family cemetery disappeared during farming operations on the property. Eventually, only ten acres out of the original 1,000 acres remained with the house. La Vista was purchased by its current owners, Ed and Michele Schiesser, in 1983.

Sources:

Boulware, A.T. Virginia Chancery Causes, Index Number 1870-009, Library of Virginia

Boulware, Alfred J. "Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, 1861-65." National Archives and Records Administration

Boulware, Alfred J. "Case Files from Former Confederates for Presidential Pardons ('Amnesty Papers'), 1865-67." National Archives and Records Administration

Durrett, Virginia Wright, From Generation to Generation: The Confederate Cemetery at Spotsylvania Court House. Durrett, Spotsylvania:Virginia, 1992.

Farmer, Selma, "Arcadia." Works Progress Administration of Virginia Historical Inventory, March 19, 1937.

Herlong, Mark W. "An Incurable Romantic: The Life and Loves of John Moore McCalla, Jr."

"Stonewall" Jackson Death Site

Ross, Helen P. La Vista Registration Form, National Register of Historic Places

Rubey, Ann Todd; Stacy, Isabelle Florence; Collins, Herbert Ridgeway. The Tod(d)s of Caroline County and Their Kin. Aircraft Press, Columbia: Missouri, 1960.