He came from a distinguished family that arrived in Spotsylvania in the early 1840s, and during his long and useful life, William Aquilla Harris made a significant mark in the community in the form of public service. He is best remembered as an excellent physician, and was my family's doctor for decades.

William was born in Spotsylvania County on December 28, 1877 to Thomas Addison Harris and the former Mary Elizabeth Poole. At the time of William's birth, Thomas was overseer of the poor for Spotsylvania. The county poor house was located off Gordon Road near Old Plank Road. I believe the overseer's house was located on the poor house property. Thomas would later serve as county sheriff for twenty years, and then served the last nine years of his life as clerk of the Spotsylvania court.

Four years after William's birth, Thomas bought a 260 acre farm that lay along a stretch of Court House Road from Brock Road north. This was the house in which William spent most of his childhood. As a young boy, Thomas had attended Shady Grove Church with his family. But now that he was established at the courthouse, he and his family became members of nearby Zion Methodist Church. In the photograph below, William Harris appears seated in front (#58):

William appears in another group portrait of that era. The photograph below was taken at Spotsylvania Court House about 1890. Shown are William (#5) and his father, Sheriff Thomas Harris (#13):

William was educated in the public school near the court house until he was 15, then was tutored by a Professor George Jenks, an Englishman. He then studied Under Dr. George Rayland of Johns Hopkins University. In 1898, William entered the Medical College of Virginia, and earned his medical degree in 1901. He was president of his class.

9126 Court House Road

Upon his graduation from medical school, Thomas gave his son a portion of the family farm on which to build a house. During that eventful year, on July 3, 1901, William married Dora Crismond, who was the daughter of Spotsylvania clerk of court Joseph Patrick Henry Crismond. They moved into their newly completed house at 9126 Court House Road in 1903. Dr. William Harris ran his medical practice from this house. William and Dora raised a son and two daughters here. This building still stands.

The Free Lance 11 January 1902

Among Dr. Harris's earliest patients was my grandfather, Horace Row, and Zebulon "Buckshot" Payne, who were injured in a buggy mishap in 1902. Buckshot was seriously hurt. Twenty years later, Dr. Harris made out the death certificate for Mr. Payne, who drank himself to death. In 1939, Dr. Harris made out the death certificate for my grandfather, who died of a heart attack in Sperryville while picking apples.

Mary Houston (1882-1916)

Three years later, Dr. Harris treated Horace's mother, Elizabeth Houston Row, while she was enjoying a visit from her niece, Mary Houston of Rockbridge County, Virginia. Upon her return home, Mary wrote a highly entertaining letter to her aunt, in which she made reference to William: "When your letter came, I was just starting to write to you. You don't know how sorry I am to know that you are not well again--I think I'll have to go back there and punch that doctor's head--he is too good looking anyway and a black eye would be just the thing for the old guy."

William Harris was an early adopter of the automobile, and as by 1910 he was making house visits by car. This experience made him an avid and long-time proponent of improving local roads. He served for a number of years on the county's road commission. He was also a member of the Automobile Association of Virginia and the Fredericksburg Motor Club.

In addition to his medical practice, William was actively involved in the civic life of his community. For a time he served as county coroner and was head of the board of health for Spotsylvania County. He served on the county school board. He was a member of the Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks. In 1912, he was appointed to the board of visitors of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute.

In March 1917, Dr. Harris wrote this letter to my great-grandmother, reassuring her about her health and telling her that she should make the trip to visit her brothers in Rockbridge County. He also comments on the recent marriage of Horace to my grandmother, Fannie Kent. (Eleven years later, Dr. Harris signed my great-grandmother's death certificate).

During World War I, Dr. Harris volunteered his services with the 304th Sanitary Train, which provided medical support for the 79th Division during its service in France. On June 30, 1918 he departed from Hoboken, New Jersey aboard USS Mongolia as a major in the Medical Reserve Corps. In June the following year he returned to the United States as a lieutenant Colonel in the MRC aboard USS Shoshone.

Member of House of Delegates, 1938

Dr. Harris served three terms in the House of Delegates, 1936-1942. It was during this time that his wife's health began to fail. Dora Harris died at their home on April 29, 1938 She lies buried in the Confederate Cemetery at Spotsylvania Court House. The following year, on October 19, 1939, William married Mattie Puckett of Russell County Virginia.

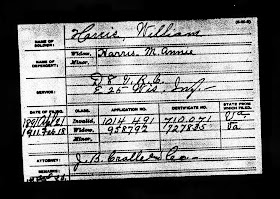

William Aquilla Harris died suddenly at home of coronary thrombosis on May 25, 1944. He is buried near Dora in the Confederate Cemetery.

After William's passing, Mattie Harris taught at Spotsylvania High School. She died on September 22, 1956. She is also buried in the Confederate Cemetery.

Links:

Biography of Thomas Addison Harris: https://spotsylvaniamemory.blogspot.com/2013/10/thomas-addison-harris.html

Biography of Joseph Patrick Henry Crismond: https://spotsylvaniamemory.blogspot.com/2011/11/strange-tale-of-jph-crismond.html