|

| 706-708 Caroline Street, Fredericksburg |

Nancy Estes Row, my great great grandmother, was one of six daughters born to Richard and Catherine Estes of Spotsylvania. Unlike her brothers, who moved west to seek new destinies, Nancy's sisters for the most part married well and remained in Spotsylvania or Fredericksburg (the exception was Polly Estes Carter who separated from her husband William because of his drinking and returned to Greenfield and lived with Absalom and Nancy Row until her death in 1863). Nancy's sister Catherine made a unique choice for her spouse and it is the story of that family that is the subject of today's post.

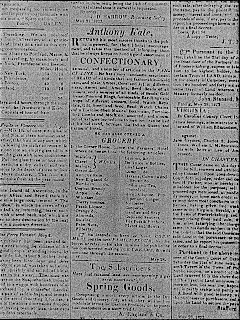

Named for her mother, Catherine Estes was born in Spotsylvania on February 17, 1794. A notice of her marriage to Swiss immigrant Anthony Kale appears in the April 10, 1816 edition of the Virginia Herald. Anthony and Catherine had at least four daughters and three sons. An artifact that has survived for more than 160 years is this doll, named "Fanny Augusta Kale" by Catherine's privileged daughters.

I do not know anything about the details of Catherine's life, so I will let this notice of her death from the October 1, 1859 edition of the Weekly Advertiser speak for itself:

|

| Obituary of Catherine Estes Kale |

|

| Headstone of Catherine Estes Kale |

Catherine is buried by her husband in the Masonic Cemetery in Fredericksburg.

|

| Chur, Graubunden, Switzerland |

Anthony Kale was born about 1790 in Chur, the capital of the Swiss canton of Graubunden. How he came to Fredericksburg, Virginia from landlocked Switzerland, what dreams and ambitions drove him to make the journey, from what European port did he sail to America, at what city did he disembark are questions for which I have no answers. I do know that the records I have show he came to Fredericksburg after 1810. We already know that he was married to Catherine Estes by the spring of 1816.

It did not take Anthony much time to fall into step with one hoary American custom that would have been at odds with his Swiss countrymen. I refer, of course, to the ownership of African slaves. The censuses from 1820-1850 show that Anthony employed both free blacks as well as slaves. In the 1820 and 1830 census he had one of each category of servant. In 1840 he utilized the labor of five slaves. In 1850 he employed two free black and two slaves.

In 1819 Anthony Kale purchased the property at 706 Caroline Street, where as a candy maker he operated a confectionery and retail grocery. In 1823 that building burned (along with many others in that section of Caroline Street). He rebuilt a three story structure there the following year on that same lot. Today that building is known as the Fredericksburg Visitors Center. During his lifetime the family lived in floors over the store. Mabel Row Wakeman wrote that he was very successful and enjoyed making candy into old age. This building was used by Federal troops to hold Southern prisoners during the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862.

|

| Advertisement from Virginia Herald 28 May 1823 |

|

| Transcription of Anthony Kale's advertisement |

In 1831 Anthony Kale built another three story building at 708 Caroline, next door to his home and business. This place was intended to be rental property and served that purpose for many years. His first tenant was Benjamin Long. The properties on Caroline Street, as well as another one on Princess Anne Street, remained in the Kale family until 1904. Anthony died in 1850 and is buried in the Masonic Cemetery in Fredericksburg.

|

| Headstone of Anthony Kale |

Anthony and Catherine Kale's oldest daughter, Marie Louisa, was born in Fredericksburg about 1818. She married neighbor and tenant Benjamin Long on January 29, 1834. He died just two short years later and Marie Louisa then married Joshua T. Taylor and lived in Washington, D.C. When she died on December 8, 1872 her remains were brought back to Saint George's Episcopal Church for her funeral. She is buried near her parents in the Masonic Cemetery.

|

| Joshua T. Taylor and Maria Louisa Kale Taylor |

|

| Headstone of Marie Louisa Kale |

|

| Monument of Marie Louisa Kale |

| |

| Mary Kale Harding |

|

| Enoch Harding |

Mary Kale was born in Fredericksburg in August 15, 1826 and married Stafford farmer Enoch Harding on March 20, 1861. They had two sons together, Milton and Cleveland and Mary outlived Enoch by more that thirty years. In her will Nannie Row left to Mary her alpaca dress and her calico dress.

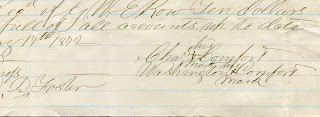

Kate Kale was the only one of her family who never married. Born in Fredericksburg in April 1830, it was she who inherited her father's properties in town, which were sold at auction after her death. The 1860 census shows that she and her sister Mary were living together in town. Years later when she was too old to be alone she moved into Mary's house in Stafford and remained there until she died. In a letter written to Roger Mansfield in 1956 Mabel Row Wakeman said that Kate and her sister Julia "were both in more than comfortable circumstances." My great grandfather George W. E. Row, turned to both of them for monetary help to fuel his cash hungry businesses. The items shown below are from his estate papers.

|

| Receipt of Kate Kale for $150 |

|

| Receipt of Kate Kale for $25 |

|

| Check to Kate Kale for $25 |

In her will Nannie Row left Kate her plaid summer shawl.

During the last years of her life Kate was afflicted with a problem so unusual that it made the pages of The Free Lance. While sleeping her jaws popped out of joint and she would require medical attention. This happened three times. After at least one stroke Kate succumbed on July 12, 1904.

|

| Julia Kale Alexander and Lucy "Lutie" Alexander |

Julia Anton Kale was born in Fredericksburg on July 27, 1833. She married Robert Brooke Alexander on September 29, 1852. Robert was publisher of the Democratic Recorder in Fredericksburg from 1857 to 1860, when it was sold to George H.C. Rowe.

Julia and Robert had one daughter, Lucy ("Lutie") who was born in 1858 and died November 7, 1861. Lutie's headstone stands with those of her parents at the Masonic Cemetery:

Dearest Lutie thou art gone.

Death has broken life's silver chain;

But to Heaven thy spirit's flown,

Where we hope to meet again.

|

| Lutie B. Alexander |

Robert Alexander was also buried in the Masonic Cemetery after his death in 1878. Julia appears to have been a lender of choice for George W.E. Row. At any rate he paid her $86.08 in 1881.

|

| George W.E. Row check to Julia Alexander 1881 |

In her will Nannie Row left Julia a photograph of her father, Absalom Row. Julia died in Stafford on July 7, 1887.

|

| Headstone of Julia Alexander |

Like their Estes uncles, all three Kale brothers moved west. William Kale was born February 26, 1819. He married Susan Ware and moved to Owen County, Kentucky. By 1840 he established a farm there near his uncle George Washington Estes (for whom my great grandfather was named). William and Susan Kale had eight children, at least four of whom did not live past the age of thirty five. Susan died in 1864. The 1880 census shows that 79 year old George Washington Estes was living with William and his children Kitty and Jeff Davis. William Kale died February 2, 1882.

The other two Kale brothers went to Texas. Richard Kale lived in Denton, where he raised stock. The 1870 census shows him living alone. Richard Estes served in the 15th Texas Cavalry during the Civil War. He died February 9, 1872 and is buried in Denton, Texas.

|

| Headstone of Richard Kale |

|

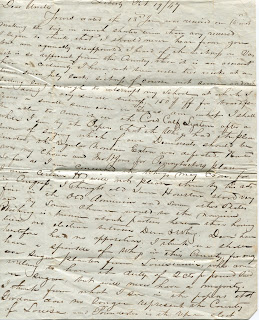

| John Kale to Absalom Row 19 February 1847 |

|

| John Kale to Absalom Row 19 February 1847 |

|

| Transcription of John Kale's letter |

|

| Transcription of John Kale's letter |

The 1850 census for Polk County shows that John was living on the farm of Harvey Sanderson and working as "Co. [County?] Clerk." It seems that John married a Mary Winifred Hicks in 1852. A son from that union, John, was born in 1862.

John Kale enlisted in the 5th Texas Infantry, part of Hood's Division, on August 24, 1861. He was sent with his regiment to Virginia, where he took sick almost right away. The records show that he was sick in the General Hospital in Dumfries in November 1861. He is still on the sick rolls in Fredericksburg in March 1862. John was shot during the battle of Second Manassas on August 30, 1862. He was taken to General Hospital No. 21 in Richmond for treatment. The rolls for October 29, 1862 indicate that John was staying in private quarters, "having furnished a substitute." There is nothing else in his military record after his hospital discharge dated November 1, 1862.

In 1867 John married Isabelle "Belle" Taylor Wallace. They had four daughters together, the last dying in childbirth with Belle on May 15, 1873.

The 1870 census shows John Kale working as a dry goods merchant in Livingston. Aunt Mabel said that he prospered during those years. And yet by 1880 he is living alone and farming. His children are not listed with him on that year's census and there is some evidence that they may have been sent to live with relatives in Mississippi. John died in Livingston, Texas in 1886.