|

| Chancellorsville |

For much of the nineteenth century my Row ancestors enjoyed many connections with the Chancellors of Spotsylvania. These were ties of friendship, public service, commerce and war. The Chancellors' place in history is forever fixed because of the unfortunate location of George Chancellor's house on the Orange Turnpike in May 1863. But it is the back story of these people's lives that adds to our appreciation of what is an already remarkable narrative.

|

| Forest Hall, courtesy of the National Park Service |

|

| Location of Forest Hall (sold to N.R. Fitzhugh 1860) |

Major Sanford Chancellor was born in Orange County on January 8, 1791 to John and Elizabeth Edwards Chancellor. He was the younger brother of George Chancellor (1785-1836), who married the widow Ann Lyon Pound Ann's half-brother, Baltimore merchant William Lorman, built Chancellorsville as a wedding present for them. Sanford's wife Frances ("Fannie") Longwill Pound, was a daughter of Ann Lyon Pound's first marriage. In the photograph above, we see several children in the front yard. Standing in the doorway are, very likely, Sanford and Fannie Chancellor (many thanks to Park historians Noel Harrison and Don Pfanz for kindly providing me a scan of this rare photograph).

Forest Hall was a plantation of 650 acres on the Rappahannock River near United States Ford. To the best of my knowledge Sanford built the house in about 1840. He is known to history as Major Sanford Chancellor because during the War of 1812 he served on the staff of General William Madison, brother of President James Madison. Sanford was a friend and colleague of my great great grandfather, Absalom Row.

Sanford and Fannie had, I believe, eleven children born between 1823 and 1847. Two sons died in 1838. Two daughters, Penelope and Frances, died of typhoid in 1864 within days of each other while staying with their uncle Dr. James E. Chancellor in Charlottesville. In addition to the large Chancellor family there also lived at Forest Hall black slaves, nineteen of them (mostly children) according to the 1850 slave census.

Sanford Chancellor had responsibilities and ambitions beyond those of husband, father and farmer. He twice served as High Sheriff of Spotsylvania County. In 1836 he was postmaster at Chancellorsville. Like Absalom Row, Sanford served as justice of the peace. He was also one of the county school commissioners, as shown on the lists below (originals at the Central Rappahannock Heritage Center).

|

| School commissioner, 1848 |

|

| School commissioners, undated and 1850 |

In the 1800s, long before there was anything resembling the Virginia Department of Transportation, the individual counties were responsible for the building and maintenance of roads and bridges within their boundaries. Able bodied men in the various magisterial districts were put on schedules to perform the work. For this they received a small daily compensation--or a commensurate fine if they failed to show up (my great grandfather George W.E. Row was once such a miscreant). One of Absalom Row's duties was to approve payment for this work. In the archives at CRHC are many such vouchers signed by Absalom Row, including this one dated July 3, 1843. Absalom approved payment of $2.50 to Sanford Chancellor for two days' service "as surveyor of the road from the United States mills to Elley's Road."

|

| Voucher for road work, July 1843 |

Without question the most interesting item I have found at CRHC is the record of an inquest held in Spotsylvania on February 5, 1854. On that day a jury, which included Sanford's nephew Reverend Melzi Chancellor, was empaneled to investigate the murder of Jacob, a slave belonging to Sanford Chancellor. On February 4 Jacob had been stabbed to death by Beverley, a slave belonging to William T. J. Richards. My great great grandfather Absalom Row, acting as coroner, conducted the inquest. Last June I wrote about this episode in detail, and you can read that

here. Shown below is the first page of the official record followed by my transcription of Sanford Chancellor's testimony.

|

| From the inquest regarding Jacob's murder |

|

| Testimony given by Sanford Chancellor, February 1854 |

Absalom Row wrote his will in January 1847. It was a good will, specific in its intentions, unambiguous, dated and signed. Unfortunately Absalom neglected to have his will witnessed. In April 1856, four months after his death, a proceeding took place in court to ascertain whether it was indeed the handwriting of my great great grandfather. Absalom's brother in law, Jonathan Johnson of Walnut Grove plantation, and Sanford Chancellor "were called and sworn in open court and severally deposed that they are well acquainted with the handwriting of the testator...and verily believe [it was] wholly written by the said Absalom Row deceased..."

|

| From the will of Absalom Row |

Sanford Chancellor died of "pulmonary disease" on February 25, 1860. He lies buried in the Chancellor family cemetery.

|

| Headstone of Sanford Chancellor |

After Sanford's death Forest Hall was sold and his widow Fannie and seven of their children moved to Chancellorsville. They were living there in May 1863 when the house was taken over by General Hooker for his headquarters. The Chancellors' youngest daughter, Susan Margaret, kept a journal of the time leading up to and including the battle of Chancellorsville. It is a most remarkable account of those days, made all the more so by the fact that Sue Chancellor was just 16 years old. Some of her story can be read

here.

Chancellorsville was partially destroyed by fire during the battle and Fannie Chancellor never lived there afterwards. She moved to Oak Grove, where she lived until her death in 1892. In September 1878 she was a customer of the saw mill of my great grandfather, George Washington Estes Row. In one of his account books is this entry for the purchase of 1000 feet of second class fencing.

|

| From a ledger of G.W.E. Row |

|

| Melzi Sanford Chancellor |

Melzi S. Chancellor was born in Spotsylvania at Fairview on June 29, 1815, the oldest son of George and Ann Lyon Pound Chancellor. It is said that his mother decided on this decidedly distinctive first name while reading a book during her pregnancy when she was struck by the name of one of the characters. Like most well-to-do boys of the time Melzi was educated in private schools. He professed his religion in 1834 while working in Baltimore as a clerk for his uncle, Alexander Lorman (46 years later Lorman left Melzi a handsome inheritance). Melzi was ordained as a minister the following year. During his long career as a Baptist minister he served as pastor at these churches in the Goshen Association: Wilderness, Piney Branch, Mine Road, Salem, Goshen, Craig's, Eley's Ford and New Hope. Craig's burned during the Civil War and was rebuilt with the aid of Reverend Chancellor.

|

| Fredericksburg Ledger, 24 August 1866 |

In addition to his ministry, Melzi also seemed to have modest political aspirations. His name appears as justice of the peace and he was also a Commissioner of Revenue for St. George's Parish.

|

| Fredericksburg News, 12 March 1852 |

Melzi married Lucy Fox Frazer in Baltimore on November 23, 1837. They had eleven children, all but one of whom would live to adulthood.

|

| Marriage register (Chancellor is at bottom) |

By the time of the Civil War the Reverend Chancellor and his family, together with seven slaves, were living in a house built by James Dowdall in 1745 and had formerly been used as a tavern and post office. Located near Wilderness Church, this place would become the focus of one of the most dramatic events of the Civil War.

|

| Dowdall's Tavern |

|

| Map detail of battle of Chancellorsville |

Melzi Chancellor's house was within the Union lines and was utilized as headquarters for General O.O. Howard. On May 2, 1863 Confederate forces led by Stonewall Jackson worked their way to the western flank of the Union army. Their circuitous route took them through Greenfield, the Row plantation, via a road now called Jackson Trail West. When the Rebel troops crashed into the utterly surprised Yankees this part of the Union army fled east in panic. A mob of them rushed to Melzi's house and "appealed to him for a place to hide. He directed a number of them to a cellar, over which was a trap door. When they were all in he shut the door down, and the Confederate troops came up in a short time and captured thirty of them." According to his obituary, Reverend Melzi Chancellor was arrested during the war and spent six months in Fort Delaware as a citizen hostage.

In 1878 Melzi, like his aunt Fannie Chancellor, was a customer of my great grandfather's saw mill business, buying two lots of oak shingles.

|

| Business envelope of George W. E. Row |

|

| Row ledger 1878 |

|

| Row ledger 1878 |

On December 5 of that same year Reverend Chancellor officiated at the wedding of my great grandparents at the home of William Stapleton Hicks.

|

| Kent-Conley wedding, 5 December 1878 |

In 1884 Melzi's wife Lucy died. Two years later he married Bettie Caldwell of Washington, D.C.

|

| Marriage license of Melzi and Bettie |

In October 1889 Melzi's daughter Lucie, wife of John J. Stephens, died. My great aunt

Mabel Row, then ten years old attended the funeral with her mother. In a letter written seventy years later to Spotsylvania historian Roger Mansfield, Mabel still vividly recalled him as "a tall man with white side whiskers."

Melzi Chancellor died on February 20, 1895. He is buried in the Chancellor family cemetery.

|

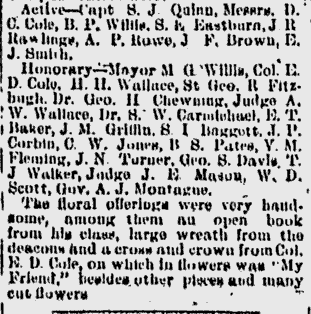

| Free Lance, 22 February 1895 |

|

| Free Lance, 22 February 1895 |

|

| Free Lance, 22 February 1895 |