.jpeg) |

| Montgomery Slaughter |

William Slaughter of Culpeper County married Harriet "Hatty" Ficklen on December 24, 1813. They made their home at a farm called "The Hermitage" in Culpeper. William was a farmer and served as the county surveyor. He was also active in the affairs of the Baptist Church and the Democratic Party. He and Harriet had at least six children together, the second of whom--Montgomery--was born on January 21, 1818.

Harriet Slaughter's brother, Joseph Burwell Ficklen, lived at "Belmont" in Falmouth (later the home of artist Gari Melchers). He owned the Belmont and Eagle flour mills, the Bridgewater Mill in Fredericksburg and the Falmouth Bridge. In 1831, young Montgomery Slaughter was sent to Falmouth to live with his uncle Joseph, from whom he learned the milling business and made many important connections in Fredericksburg, where the rest of his family moved in the early 1840s.

William Slaughter served for many years as a magistrate in Fredericksburg and was also for a time the town's assessor. Young Montgomery would in time also share his father's interest in public affairs and in public service. With the help of his uncle Joseph, Montgomery built the foundation for a long and prosperous career as a miller and merchant.

Montgomery's name could be found in the newspapers by the early 1840s. In March 1843 his name appeared in the Richmond Whig, which named him among a gathering of Fredericksburg citizens protesting the passage of a recent tax bill by the House of Delegates. Three years later, the December 17, 1846 edition of the Alexandria Gazette reported that Montgomery was voted secretary at a meeting of the Fredericksburg members of the Whig Party. Montgomery's long involvement in politics was already underway.

On May 6, 1845 Montgomery married Eliza Lane Slaughter of Rappahannock County. They made Fredericksburg their home, where they had ten children together (three of whom would not reach adulthood). Unlike his parents, who were devout Baptists, Montgomery and Eliza became parishoners at St. George's Episcopal Church, where Montgomery served on the vestry.

|

| Alexandria Gazette, 12 May 1845 |

By 1848, Montgomery owned a successful retail business on Commerce (today's William) Street. He was also making his presence felt as a miller, producing his own flour at the Belmont and Eagle mill, whose facilities he rented. He also shipped his products to such commercial centers as Baltimore and New York.

|

| Fredericksburg News, 14 November 1851 |

|

| Fredericksburg News, 8 August 1853 |

Montgomery was involved in other business enterprises as well. He was an investor in the Liberty Mining Company, a venture that did not turn out well. In 1855 he was named to the Board of Directors for the local branch of the Bank of Virginia. He was also commissioner of the Fredericksburg Power Company, which provided water power to Bridgewater Mills and other such places in town.

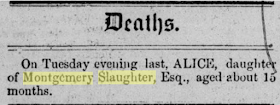

A number of disasters befell the Slaughter family during the 1850s. Montgomery and Eliza's infant daughter died on August 9, 1850. On November 3, 1856 another daughter, Alice, died of whooping cough. And in February 1859 a fire started in the carpenter shop of William Baggot. The wind quickly spread the blaze to the Slaughter house, which was destroyed. Fortunately, Montgomery carried an insurance policy valued at $2,000 with the Mutual Fire Insurance Company.

|

| Fredericksburg News, 13 August 1850 |

|

| Fredericksburg News, 13 November 1856 |

|

| Lynchburg Daily Virginian 4 February 1859 |

In 1857, Montgomery bought "Westwood," an eighty two-and-a-half acre farm in Spotsylvania that lay about two miles from the town's limits. This farm was adjacent to the property that is known today as Hazelwild.

|

| Alexandria Gazette, 10 November 1859 |

|

| Richmond Daily Whig, 29 August 1860 |

Like the John Brown raid the year before, the election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency goaded southerners to take immediate and highly consequential action. The fire-eaters of South Carolina were the first to take their state over the precipice of secession. Virginians took a more cautious approach to the fateful step of leaving the Union. Meetings on the this momentous topic took place in town halls across the state. On Monday, December 17, 1860 Mayor Slaughter presided over a meeting in Fredericksburg to discuss and to take action on proposed resolutions "in relation to the present crisis in our nation." The resolution paid lip service to the notion of some sort of reconciliation with the national government, but made clear that the inviolability of Virginia's perceived constitutional rights took precedence over the survival of the Union. The resolution called for the creation of a convention in Virginia that would seek the cooperation of other Southern states in the formation of a Southern convention to take the necessary steps to preserve their rights if they were confronted with "force or coercion" from the national government.

|

| Alexandria Gazette, 20 December 1860 |

An Ordinance of Secession was passed by the Virginia Convention on April 17, 1861. A popular referendum on May 23 ratified the act of secession, but of course by then Virginia was already at war and had offered Richmond as the capital of the newly-created Confederate States of America.

On April 19, 1861, Montgomery Slaughter, James B. Ficklen and D.H. Pannell were standing at a cross-street in Baltimore when a regiment of Massachusetts volunteers arrived at the train station. They were among the many of the units that answered the call of President Lincoln to come to the defense of Washington, DC. While in Baltimore these Massachusetts troops were set upon by a pro-Confederate mob, who hurled bricks and stones at the volunteers, who fired into the crowd. Six soldiers were killed and 12 members of the mob also lost their lives.

|

| Richmond Enquirer, 23 April 1861 |

It would be another year before Fredericksburg would be seriously threatened by the presence of Federal troops. In the meantime, the Common Council began to take steps to prepare for that eventuality. On April 19, 1861 the Council voted to borrow $5,000 to raise and equip a city Home Guard, and it was ordered that two cannons owned by the town should be put into working order. On June 10, the Council passed a resolution to set aside $500 to "supply the necessities of life" to those families in town who had relatives serving in the Confederate army. On December 28, steps were taken to accommodate the encampment of the 30th Virginia Infantry which would spend some time in Fredericksburg. The officers would be housed in the Courthouse, and a kitchen and privies would be built on the Courthouse grounds.

The war arrived at the town's doorstep on April 18, 1862, when Union troops advancing from Warrenton arrived at Stafford Heights. The Confederates who had been defending that area fled across the Rappahannock, burning the Falmouth, Chatham and RF&P Railroad bridges to impede the enemy's progress across the river. A couple of steam boats were also sunk at Ferry Farm, across from the city dock. The U.S. army now commanded the heights overlooking the town. The image below shows the ruins of the Falmouth bridge, and the locations of Belmont and the Eagle and Belmont mills.

|

| (Courtesy of John Hennessy) |

Within days, U.S. forces occupied Fredericksburg and remained in the town for the next four months. Their presence would have a serious impact on the local economy, as well as for a number of the town's leading citizens, resulting from an unfortunate incident that arose from the Confederates' intolerance for those who still professed loyalty to the United States.

This prolonged presence of the U.S army in Fredericksburg led to the collapse of the slave economy in the region. As word of its proximity spread through the nearby counties, slaves began to flee the plantations and make their way to their perceived source of freedom. Over the course of the summer, some 10,000 enslaved people found refuge within the Union lines. Many would later spend time in camps set up for them in Alexandria and Washington. From there, they moved on to their new destinies. The sudden and wholesale disappearance of their main source of labor sent shock waves through the white community; for many of them, the ownership of slaves was their primary financial asset.

|

| Alexandria Gazette, 14 July 1862 |

During late 1861 and early 1862, Confederate authorities in Virginia thought it would be a good idea to arrest a few dozen of the state's citizens and confine them in Castle Thunder Prison in Richmond. Their crime? They refused to take an oath of loyalty to the Confederate States and continued their allegiance to the nation of their birth, the United States.

|

| Castle Thunder |

Among those arrested were several from Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania: Major Charles Williams, Peter Couse, Squire Ralston, Buckingham Wardwell, A.M. Pickett, Moses Morrison and his brother Thomas Love Morrison. The experience of Peter Couse was probably quite similar to that of the other unfortunate Union loyalists. Confederate General Theophilus Hunter Holmes, commander of the Fredericksburg and Aquia District early in the war, ordered the arrest of Peter Couse. On the night of March 6, 1862, Captain Corbin Crutchfield of Company E of the 9th Virginia Cavalry oversaw the arrest of Peter and hauled him down to Castle Thunder.

Peter and his fellow prisoners would languish in prison for more than six months. The plight of these poor fellows did not go unnoticed. During the occupation of Fredericksburg during the summer of 1862, an opportunity presented itself to take steps to free the Union loyalists in Richmond.

|

| Levi C. Turner |

|

| Lafayette Curry Baker |

On August 9, 1862, Judge Advocate General Levi C. Baker wrote a letter to Lafayette Curry Baker, a Union investigator, spy and soon-to-be provost marshal of Washington, DC. In his letter, Turner ordered Baker to make arrangements for the arrest of a number of the leading citizens of Fredericksburg, including Mayor Slaughter, and hold them in custody as hostages to guarantee the safe return of the Unionist prisoners in Richmond.

|

| Levi Turner letter to Lafayette Baker |

On the night of August 13, 1862 Union soldiers rounded up 12 men, including Mayor Slaughter, and took them to the Farmers Bank building on Princess Anne Street (more commonly known now as the National Bank, and then PNC). They were assisted in locating some of these men by John Washington, a slave who had escaped into Union lines soon after arrival in Fredericksburg in April. These captives were then placed aboard the steamer Keyport and, guarded by a squadron of men from General Burnside's division, were brought up the Potomac River and immediately taken to the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, DC. There they joined seven other Fredericksburgers who had been arrested previously. Those seven men were:

-Thomas B. Barton, attorney

-Thomas F. Knox, wheat speculator and flour manufacturer

-Beverly T. Gill, retired tailor

-Charles C. Wellford, dry goods merchant and owner of the Catharine Furnace

-James McGuire, merchant

-James H. Bradley, grocer and deacon of the Fredericksburg Baptist Church

-Reverend William F. Broaddus, pastor of the Fredericksburg Baptist Church

The men who were arrested on August 13 were:

-George Henry Clay Rowe, attorney

-Montgomery Slaughter, merchant, miller and mayor

-John Coakley, retired merchant and superintendent of the Fredericksburg Aqueduct Company

-Benjamin Temple, farmer

-John Francis Scott, owner of the Hope Foundry

-John H. Roberts, well-to-do former Whig

-Michael Ames, blacksmith

-John J. Berrey, hardware store owner

-Abraham Cox, tailor

-William H. Norton, carpenter

-James Cooke, merchant and druggist

-Lewis Wrenn, merchant

|

| Old Capitol Prison |

On August 19, G.H.C. Rowe wrote a letter on behalf of all 19 prisoners to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. Rowe sought specific information regarding the legal grounds for their confinement, and if they would be released when the Unionists in Richmond were let go.

|

| G.H.C. Rowe letter to Stanton, 19 August 1862 |

G.H.C. Rowe and John F. Scott then each wrote a letter to Secretary Stanton asking to be released from Old Capitol Prison in order to go to Richmond and negotiate for the release of the Unionist captives, who would then be brought to Washington and exchanged for the 19 Fredericksburg men.

In his book "The History of the City of Fredericksburg," Silvanus Quinn noted that U.S. authorities paroled Reverend Broaddus for the purpose of effecting the release of Major Williams and Mr. Wardwell from their prolonged imprisonment in Richmond. Reverend Broaddus met with Richmond jurist Beverly R. Wellford. Together they met with Confederate Secretary of War George W. Randolph, who ordered the release of the two prisoners sought by Broaddus and Wellford. Reverend Broaddus returned to Washington, thinking that he had successfully negotiated a prisoner swap.

However (according to Quinn), U.S. officials changed the rules of the exchange by demanding the release of two other men as well. And so began a protracted and difficult series of negotiations that ultimately led to the release of the 19 hostages.

On the other hand, contemporary newspaper accounts provide a different view of how this was resolved. The September 25, 1862 edition of the Alexandria Gazette gave credit to Mr. Rowe for the release of the hostages: " Yesterday, Mr. G.H.C. Rowe of Fredericksburg, a prisoner (who was seized by Union authorities and with others was held as a hostage for the release of Union citizens) returned from Richmond, whither he went on parole, to effect an exchange of prisoners on both sides. General Wadsworth [James E. Wadsworth was at the time the military governor of the Washington district] has exerted himself for two months past for this accomplishment." Under military escort, Rowe brought more than two dozen Unionists to Washington, and the exchange was made.

According to Quinn, the freed Fredericksburg hostages were placed on a steamer, which brought them down the Potomac and dropped them off at Marlborough Point in Stafford County, "from which they walked to town to greet their family and friends. There was great rejoicing on their return, and the whole population turned out to meet them and give them a cordial welcome."

By early September 1862, all the Union troops in Fredericksburg and Stafford were withdrawn to confront the threat of Confederate forces converging on Maryland. Once the danger of the Confederate presence there was neutralized by the outcome of the Battle of Antietam, the Union army was once again in a position to shift its strength back to Stafford Heights, which it occupied on November 17. On November 20, at the request of General Robert E. Lee, Mayor Slaughter and two members of the Common Council met with the Confederate Commander-in-Chief at Snowden. The following day, a letter written by Union General Edwin V. Sumner was delivered to the mayor and members of the Council at an impromptu meeting held at the foot of Hawke Street. Written at the direction of General Ambrose Burnside, the letter demanded the surrender of the town by 5 p.m. or Union artillery would commence shelling the town. Mayor Slaughter forwarded the letter to General Lee, and shortly before the deadline asked for additional time to evacuate the civilians from the town, which was granted. In due course, many families packed wagons with whatever valuables they could carry and fled the town. The fortunate ones were able to find shelter with friends and family in Spotsylvania. Others were obliged to camp outdoors in frigid conditions. A large number of them encamped on the grounds of Salem Baptist Church.

On December 11, 150 cannons began firing into Fredericksburg from Stafford Heights. Those civilians who had not fled to safety cowered in terror in their cellars. A great many homes and businesses were damaged or destroyed during the bombardment. Among these was the home of William Slaughter, the mayor's father.

|

| Alexander Gazette, 26 December 1862 |

|

| Damaged homes at Hanover and George streets |

|

| Wartime view of Fredericksburg Baptist Church |

The following day, U.S. troops occupied Fredericksburg once again. They used this opportunity to pillage the town and inflict further damage to the mostly abandoned town. An alcohol-fueled orgy of theft and violence continued into the night.

On December 13, 1862, thousands of U.S. soldiers mounted a series of fruitless attacks against Confederate forces entrenched on the high ground just outside the town. The huge number of casualties suffered by the Federals meant that virtually every intact building in Fredericksburg was utilized as a hospital. Eventually, these suffering men were transported across the river to Stafford and ultimately were conveyed by steamers up the Potomac to hospitals in Alexandria and Washington, DC. Although a large number of Union dead were carelessly buried under a flag of truce, many remained above ground, including several on the porch of Mayor Slaughter's house.

|

| Wilmington Journal, 1 January 1863 |

The now-impoverished civilians of Fredericksburg who had fled before the battle returned to a scene of utter devastation. Homes, businesses and infrastructure lay in ruins. With the local economy now in shambles, there was no way to provide for the most basic needs of the people. In early 1863, the Common Council organized a committee to collect and distribute money for the relief of the destitute civilians. Montgomery Slaughter was the treasurer of the relief fund. Over a period of time, thousands of dollars were collected from the residents of Richmond and other cities, as well as the generous donations made by Confederate soldiers.

|

| Richmond Whig, 23 February 1863 |

|

| Richmond Sentinel, 16 April 1863 |

In the midst of the burdens of his obligations as mayor and the destruction visited upon Fredericksburg, tragedy once again befell the Slaughter family. On July 9, 1863, seven-year-old Montgomery "Montie" Slaughter, Jr., died of scarlet fever at Westwood, the family farm. He was buried in the Fredericksburg City Cemetery near his sisters Ellen and Alice.

|

| Richmond Enquirer, 17 July 1863 |

During the Civil War, Montgomery sold commodities from his farm to various quartermaster officers of the Confederate army--timothy hay, corn, mill feed and the like. He sold sweet potatoes to the 1st Division Jackson Hospital in Richmond, and he sold coats, blankets, shirts and pants to the Confederates.. He also received compensation for firewood and plank fencing taken by troops encamped at or near Westwood.

During the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863, Union troops commanded by General John Sedgwick once again crossed the Rappahannock and attacked Confederate troops defending Marye's Heights. On this occasion, the Union army was able to brush aside the small Confederate force defending the heights. The Federals then proceeded down the Orange Turnpike in order to assist General Joseph Hooker, who was headquartered at Chancellorsville. Sedgwick's men made it as far as Salem Baptist Church, where they were repulsed in heavy fighting and were obliged to retreat back over the Rappahannock River. During the fighting near Chancellorsville, John F. Scott (who had been one of the hostages seized in 1862) assisted a reporter from Richmond by taking notes on the fighting. Scott managed to get himself captured again while working as an amateur reporter. He was once again hauled off to the Old Capitol Prison, where he was held for several days before being released.

A year later, the war would again return to Fredericksburg's doorstep. In May 1864, a series of pitched battles took place in the Wilderness and near Spotsylvania Courthouse. Unlike the fight at Chancellorsville the year before, these battles would change the course of the war in Virginia.

When the Union army moved down Catharpin and Brock roads towards Todd's Tavern, about 60 northern soldiers became separated from their regiments and found themselves stranded in the Wilderness. These men--some of them walking wounded, some of them armed, some of them skulkers--made their way east on the Orange Turnpike toward Fredericksburg. Their goal was to reach the ford near Falmouth and cross the river to reach their old encampments.

As these isolated U.S. soldiers trudged into Fredericksburg, some of the town's leaders made the ill-considered decision to capture them. A posse of armed men was quickly assembled, and the unlucky men in blue were surrounded and disarmed. They were then escorted to the nearest Confederate outpost. From there, they were marched to Richmond, where they were imprisoned.

At the time, there was a difference of opinion as to who was primarily responsible for the apprehension of the soldiers. Fredericksburg merchant Edward L. Heinichen blamed John F. Scott. In his memoir, Heinichen wrote: "A thin stream of bluecoats, some single, some in small groups, some wounded, but most of them obviously skulkers, some armed, most of them not, entered the town from the direction of Chancellorsville very meekly and inquired the way across the river, where they [wished to wade] at a ford above the town. All bridges being destroyed they interfered with nobody, and nobody interfered with them, until Mr. John F. Scott very foolishly and against the protest of Mr. Little and myself, that no civilian should take part, gathered together some other fools, who took a number of these men prisoner, and escorted or sent them to Richmond, for which act Mr. Scott suffered seriously afterwards."

The northern press, on the other hand, lay the blame squarely on the shoulders of Mayor Slaughter. It seems possible that Montgomery himself thought that he might face consequences in this incident. Just before Union troops arrived in Fredericksburg en masse, Montgomery absented himself from the town and, like Mr. Scott the year before, made himself useful as a correspondent observing the movement of troops for the Richmond Examiner and the Daily Mail. He wrote his dispatches from Guiney's Station, reporting on the fighting near Spotsylvania Courthouse. The stigma that attached itself to Montgomery's reputation remained with him long after the war.

|

| Daily National Republican, 16 May 1864 |

As it was during the Battle of Fredericksburg a year and a half earlier, the town was once again transformed into a vast hospital for the thousands of wounded U.S. soldiers transported from the killing fields of Spotsylvania. When Federal authorities learned that some of their wounded men had been captured by local civilians acting as a guerilla force operating in their rear, they were outraged. It was ordered that 62 of the town's leading citizens be arrested and held as hostages to be kept in confinement pending the safe return of the soldiers imprisoned in Richmond. Once again, Fredericksburgers were transported to the Old Capitol Prison. Ten of these men were released shortly thereafter. Among the hostages of 1864 were some of the same unlucky men who had suffered a similar fate in 1862--James H. Bradley, Thomas F. Knox and James McGuire. The remaining 52 hostages were sent to Fort Delaware, the Federal military prison located on Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River, including 1862 hostages Abraham Cox and Lewis Wrenn.

On May 31, 1864, the Common Council of Fredericksburg appointed Mayor Slaughter and John F. Scott as a committee to travel to Richmond in order to negotiate for the exchange of the soldiers and the hostages held at Fort Delaware. In the course of a series of meetings with Confederate authorities, a number of difficulties were encountered. As a result, the very able attorney George Henry Clay Rowe was called upon to iron out the complications in negotiations both with the Confederates in Richmond and with Federal officials in Alexandria. On June 20, the Common Council received a report from Rowe, who had met with Colonel H.H. Wells, the provost marshal in Alexandria. It was agreed that Rowe would oversee the transportation of the soldiers, as well as some officials from West Virginia, to Alexandria. Rowe would then receive the Fredericksburg hostages, who had been returned to the Old Capitol Prison from Fort Delaware. The story of the travel of the soldiers and the West Virginia men to freedom was described in the July 6, 1864 edition of the Soldier's Journal:

On July 8, 1864, G.H.C. Rowe delivered 56 Union prisoners of war and the civilian officers from West Virginia to Alexandria. In return, Rowe took custody of the Fredericksburg hostages. They were placed on the steamer Weycamoke and transported down the Potomac River to Split Rock near Marlborough Point in Stafford, from which place they made their way home to Fredericksburg.

Not long after the evacuation of the Union wounded to hospitals in the Washington, DC region, the Union army instituted an occupation force in Fredericksburg that remained in place until early April 1869. The commanding officer of this force made his headquarters at the Farmer's Bank building on Princess Anne Street. The provost marshal also kept his office there.

From the beginning of the occupation, Federal authorities worked with the Common Council to achieve mutually desired goals. One of the first priorities was to improve the sanitary conditions in the town. One can only imagine the condition of the streets and the shattered buildings after prolonged stays by thousands of active troops and wounded men. For the most part, the town leaders got along well with their counterparts in the Union army. The same could not be said for relations with the enlisted men, who--at least for a time--felt at liberty to indulge in acts of violence and thievery.

An example of how cooperation between Mayor Slaughter and the military commander of the town worked well is found in the August 10, 1866 edition of the Richmond Daily Dispatch. For some reason, bad feelings existed between the burial crews working at the newly established National Cemetery on Willis Hill and the U.S. soldiers. Quick action on the part of the mayor and Major Nicodemus averted what could have been a bloody and destructive riot:

On the other hand, there were instances in which the mayor was unwilling to exert himself to cooperate with his military counterparts. In June 1866, Henry Carter Lee, a nephew of General Robert E. Lee who had served as an adjutant to several Confederate commanders during the war (including his brother, General Fitzhugh Lee) caused a disturbance in Fredericksburg. It was an incident that highlighted the precarious status of recently freed slaves and the ambivalence of officials like Montgomery Slaughter to protect them from harm.

|

| Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, 12 June 1866 |

|

| Henry Carter Lee (1842-1889) |

Although it would take many years for Fredericksburg to recover from the war, progress began to be made shortly after the collapse of the Confederacy in 1865. The RF&P Railroad, Chatham and Falmouth bridges were rebuilt. The burnt hulks of the schooners sunk in the Rappahannock opposite the city dock were removed, allowing for unimpeded navigation in the vicinity of the town. The tempo of business life began to quicken, thanks in part to the influx of northern entrepreneurs seeking opportunities for quick gains in the ashes of he old South.

As one might expect, the highly capable Montgomery Slaughter benefited from this rising tide of comparative prosperity. He continued to prosper in his milling business. He received a presidential pardon from Andrew Johnson, which enabled him to more freely participate in public life. Work resumed on the Fredericksburg & Gordonsville Railroad, which was later known as the Potomac, Fredericksburg and Piedmont Railroad when it finally linked Fredericksburg and the town of Orange in 1877. Montgomery served on its board of directors and was for a time its president. He was also elected to the board of directors for the Alexandria and Fredericksburg Railroad. In 1871 he was named as an incorporator of the newly revived local branch of the Bank of Virginia.

|

| Presidential pardon of Montgomery Slaughter |

On May 19, 1866, Montgomery Slaughter's father William died. He was buried near his grandchildren in the Fredericksburg City Cemetery.

|

| New Era, 22 May 1866 |

In 1867, Montgomery sold his farm Westwood to Delaware native Samuel L. Eastburn. Three years later, Eastburn sold Westwood to Moses Morrison, who had been one of the Unionists arrested by the Confederates during the hostage crisis of 1862.

In early 1868, Montgomery was elected mayor of Fredericksburg for the ninth time (in those days, the mayoral elections were held annually). By this time, the Radical Republicans in Congress were fed up with President Johnson's lenient treatment of ex-Confederates. Pressure was exerted on General John Schofield, the military governor of Virginia, to replace civic officials with men whose political reliability could be counted on. Because of lingering suspicions regarding his role in the 1864 hostage crisis, as well as the fact that he had not taken the Iron Clad Test Oath of 1862, Mayor Slaughter was a prime candidate for removal from office. On April 28, 1868, Schofield replaced Montgomery Slaughter as mayor with Charles E. Callam, a native Englishman who had served on General Burnside's staff during the war. At the time of his appointment to the mayoralty of Fredericksburg, Mallam was serving as the whiskey inspector for the regional military authority based in Alexandria. As it so happened, Mallam was a genial and easy-going person, and he got along well with the residents of Fredericksburg.

|

| Announcement of the partnership of Montgomery and William Slaughter |

His political career now over (at least for now), Montgomery focused his energies on his long-standing milling business. In 1871, Montgomery's son William joined him as a partner in his business, which was now known as Slaughter & Son. In May 1873, the Slaughters bought for $7,050 the Excelsior Mill on the Rappahannock. The mill had been owned by John L. Marye, the owner of Brompton, the house at Marye's Heights. The 1863 photograph below, from the collection of the Huntington Library, shows the Excelsior Mill adjacent to the ruined bridge of the RF&P Railroad. The white columns of Brompton can be seen in the distance.

|

| The Daily News, 10 May 1873 |

Seven months after the purchase of the Excelsior Mill, tragedy once again visited the Slaughter family. Montgomery's wife Eliza died on December 2, 1873. She was buried near her children--Ellen, Alice and Montie--in the Fredericksburg City Cemetery. By coincidence, her death notice and an advertisement for Slaughter & Son appeared on the same page of the December 4, 1873 edition of the Fredericksburg News:

As if a harbinger of more bad news to come, the canal that supplied water to the Excelsior Mill was the scene of the death of young Willie Armstrong in the summer of 1874

In 1875, Slaughter & Son declared bankruptcy. The root cause may have had something to do with the manner in which the funding for the purchase of the Excelsior Mill was structured. In any event, it was a complicated case that was followed closely by the newspapers at the time.

|

| Richmond Daily Dispatch, 25 November 1875 |

In January 1882, Montgomery's professional life took an entirely new direction when the House of Delegates voted for him as the new judge of the Corporation Court (that is, city court) of Fredericksburg. He served capably in this new role until 1888, when he was replaced by Judge Alexander Wellington Wallace.

|

| Richmond Daily Dispatch, 15 January 1882 |

|

| Judge Montgomery Slaughter |

After his retirement from the bench, Montgomery lived quietly at his home in Fredericksburg. He suffered a series of strokes in 1897 and died suddenly while at home on December 7, 1897. He was buried in the Fredericksburg City Cemetery near his wife and their children. Inexplicably, the dates for Eliza on their shared headstone are incorrect.

|

| The Free Lance 9 December 1897 |

|

| (Find a Grave) |

Sources:

John Hennessy, Looming Yankees: The Union Army Hovers Near Fredericksburg

John Hennessy, Is This the Most Important Civil War-era Building in the Fredericksburg Region?

"Minutes of the Common Council of the Town of Fredericksburg," transcribed and annotated by Erik F. Nelson. Fredericksburg History & Biography (multiple volumes)

Silvanus Jackson Quinn, The History of the city of Fredericksburg, Virginia

Edward L. Heinichen, "Reminiscences of the Civil War," transcribed and annotated by Josef W. Rokus. Fredericksburg History & Biography, Volume 6, 2007.

No comments:

Post a Comment