|

| Kent house, 1940s |

Today I wish to begin by acknowledging my indebtedness to two persons whose decades of family history research and preservation of a vast archive of photographs are true marvels. Virtually everything I have learned about the Kent side of my family is due to the generosity of my cousins and fellow researchers, Kathleen and Donald Colvin of Spotsylvania. Their encyclopedic knowledge of their extended family, including the Kents, is an important part of the fabric of Spotsylvania history. Much of the narrative below comes from the stories told to Kathleen by her beloved grandfather, William Lee "Willie" Kent (1862-1949).

|

| Anvil of Warner Kent |

Warner David Kent, my great great grandfather (and grandfather of Fannie Kent) was born on June 5, 1811 in Fluvanna County, Virginia. His early years were spent working as a blacksmith, apprenticing at the foundry of Warner Baltimore, for whom he was named. On February 20, 1834 Warner married Susan Anderson Jordan of Louisa County. Their first three children died in infancy. Next were born John Wesley (1840), Samuel Rice (1841) and Susan Jane (1847). By 1852 Warner had developed a persistent cough from working in the foundry and was looking for a new opportunity when he saw a notice in a newspaper advertising a farm available to rent in Spotsylvania. So Warner and Susan loaded up their wagons and with their young children and their worldly goods, including pear seedlings and flowers brought by Susan, moved to Spotsylvania. Their next child, William Franklin Kent (Fannie Kent's father) was born in Spotsylvania the same year they moved. Another child was stillborn in 1854 and was the first to be buried in the Kent family cemetery. Their youngest son, Columbus, was born in 1857.

Warner rented the 300 acre farm, situated adjacent to Hazel Hill near Shady Grove Church, for nine years. When it became available for purchase he bought it in November 1861. Unlike many of his neighbors, Warner was not an enthusiastic owner of slaves. The 1850 Federal Slave Census shows him owning only two and by 1860 he is not shown in the records as owning any at all.

Before the Civil War Warner's son John Wesley was the schoolmaster at the neighborhood school organized at Hazel Hill. He was also a member of the Fredericksburg Militia. He married Martha Catherine Hicks in 1861 and their son William Lee Kent was born the following year. At the outbreak of hostilities he and his brother Samuel enrolled in the 55th infantry. Samuel contracted measles and pneumonia while in Fredericksburg and word was sent to Warner that his son was desperately ill. Warner hitched up his team and drove his wagon into town and brought Samuel home, but by then there was little that could be done. Private Samuel Rice Kent died on May 5, 1862 and was buried in the family graveyard.

On May 8, 1864 Warner Kent was arrested by Federal forces while he was plowing in his field. That same day the Union army also apprehended three other civilians in the area in an attempt to prevent southern sympathizers from communicating their troop movements to the Confederates. Warner was not allowed to tell his family that he was being taken away. He unhitched his horse from the plow, mounted him and was led away by his captors. Warner's wife and young children had no idea what had happened to him. or for that matter whether he was dead or alive.

Now that there were no adult males on the Kent farm, its inhabitants and its property were vulnerable to the predations of the Northern troops swarming in that area for the next several days. On one such occasion Susan Kent was being interrogated downstairs by a Union lieutenant while one of his subordinates went rummaging around the house. Susan's daughter Jane found him upstairs placing upon a counterpane a number of the family's possessions he had taken a fancy to. He gathered up his booty and began to make his way out of the room when he was confronted by seventeen year old Jane, a tiny girl not five feet tall. A struggle ensued whereby Jane grasped the counterpane and the two tugged at the bundled Kent possessions. Jane managed to maneuver the soldier to the head of the stairs and at the opportune moment let go of her end of the blanket. The thief went tumbling down the stairs and landed in a heap at the feet of the lieutenant, who sent him outside without his loot.

|

| Kent pie safe. Photo courtesy John Cummings |

Not long after this episode the Federals returned, although this time it was presumably to ensure the safety of Susan and her children as there was still considerable violence occurring in the vicinity. The Union officer commanding this squadron saw to it that the house, the barn, the corn crib and the meat house were nailed shut and water and forage were provided for the Kent's livestock. The Kents were then led off to the Hurkamp place where they stayed for several days.

When they returned home, they discovered that the house and the outbuildings had been broken into. All the family's stores of food had been stolen. The house had been ransacked and the top of the pie safe had been chopped open in the frenzied search for food and valuables. The livestock which had not been stolen had been run off into the woods. Susan Kent found some corn meal on the ground from one of the torn sacks. She was able to sift most of the dirt out of it and make some corn pone from it. Susan scraped the dirt from the earthen floor of the meat house and put it into boiling water in order to reclaim whatever salt might be present. To provide meat for her children Susan was reduced to throwing rocks at squirrels and rabbits.

|

| Records of the Old Capitol Prison |

Meanwhile, Warner Kent was still a prisoner of the Union army as his captors made their way around Spotsylvania. Along with the other men who were captured the same day as himself (Joseph Hall, Thomas Manuel and W.W. Jones), Warner was sent to Aquia Landing and ultimately was jailed at the Old Capitol Prison in Washington City. In the prison log Warner Kent is identified as a "suspicious character."

|

| Letter to Edwin Stanton 13 June 1864 |

|

| Letter to Edwin Stanton 13 June 1864 |

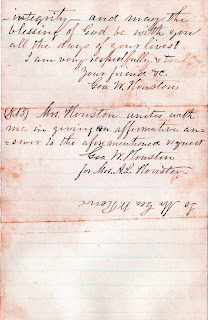

The brother in law of one of Warner's fellow prisoners began to advocate for his release and it finally dawned on the Federal authorities that they had no real cause to hold them. Letters and petitions were sent to Secretary of War Stanton, including the one above written by Judge Advocate L.C. Turner. Warner was offered his freedom in exchange for signing an oath of allegiance. Warner objected, saying that doing so would put both his reputation and his physical safety in jeopardy once he was freed. He was allowed to sign a document in which he promised not to give assistance to the Confederacy in the future. The portions of that paper which would have obligated him to pledge loyalty to the Union were stricken out. He promised "that I will do no act hostile or injurious to the union of the States; that I will give no aid, comfort, or assistance to the enemies of the government, either foreign or domestic..." An order for Warner's release was signed on July 15, 1864.

|

| Oath of Warner Kent |

Warner Kent was finally free to return home, but he would have to do so without his horse. The 53 year old was obliged to walk all the way from Washington to his home in Spotsylvania. Warner would later say that he was treated relatively well as a prisoner, but he remained angry over the fact that he was not allowed to tell his family that he was being arrested and that they would have to fend for themselves, not knowing his fate.

The final Kent casualty of the war occurred almost a year later when Warner's son John Wesley Kent was captured at Harper's farm during the battle of Sayler's Creek on April 6, 1865. Had he not been captured that day and had been able to accompany Lee's army to Appomattox, John's fate would have likely been quite different. However, John and the other Confederate prisoners of that engagement were marched off to captivity. John was imprisoned at Point Lookout, Maryland. There he fell victim to one of the many diseases rampant in such prisons. He never fully recovered. He was finally released on June 8, 1865 and soon thereafter came back home to Spotsylvania, "broken in body and spirit." John Wesley Kent died New Year's Day 1867 and was buried in the Kent cemetery. He was followed two years later by his brother Columbus, who died of cholera in 1869.

|

| William Lee "Willie" Kent |

|

| William Franklin "Billy" Kent |

|

In the years that followed, the Kent farm, called "The Oaks", was divided between Warner's son Billy Kent and his grandson Willie Kent. Billy Kent built a new house for himself, while Willie took the part of the farm that included Warner's house and all the outbuildings. As Warner grew older, he took up residence in the room over the carriage house. Willie wished for him to have a stove for his comfort, but his grandfather preferred the open fireplace he was accustomed to. Even though he was by now in his nineties, Warner still insisted on tending to his fire despite the fact that he was now too infirm to do so safely. One day while tending his fire he lost his balance and fell into the fireplace. Willie was burned pulling his grandfather from the flames, but he recovered. Warner did not, and died on November 9, 1906.

|

| Fredericksburg Free Lance 13 November 1906 |

|

| Plaque at the Kent family cemetery |