|

| Map detail of southwestern Stafford County, 1860s (Fold3.com) |

In addition to the innumerable dead and wounded during the Civil War, the suspension of many of the freedoms and legal protections white Americans had enjoyed since the founding of the Republic added another layer of misery to people's lives. In the Confederacy, little tolerance was shown to anyone who was still loyal to the government of the United States, or to those who wavered in unconditional support for slavery. During the administration of Abraham Lincoln, long-cherished ideals such as freedom of the press, freedom of speech and assembly, and the right to a fair and speedy trial were swept aside in the cause of restoring the Union. In both the north and the south, anyone suspected of sympathizing with the "wrong" side could expect a harsh response.

One person who suffered such a fate was Sarah E. Monroe of Stafford County. By early spring of 1864, she was a young widow with four children and an elderly mother, living in southern Stafford "two and a half miles from the Chancellorsville battlefield." In the Civil War-era map detail above, what I believe to be her home is shown in the upper left of the image, above U.S. Ford. Pinning down precise dates and associations regarding Sarah's life was no easy task, but I believe that her late husband was farmer Frank Monroe, who was a private in the 47th Virginia Infantry. The last entry in his compiled service record shows him to be in the Confederate hospital in Winchester suffering from typhoid fever. He died on November 24, 1862.

|

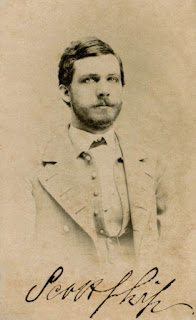

| Levi C. Turner |

Unfortunately for Sarah, her existence was brought to the attention of Levi C. Turner, associate judge advocate for Washington DC and the surrounding region. It was reported to him that Sarah was disloyal, and had been "harboring rebels--rebel scouts, etc." Furthermore, Turner was of the opinion that "she was a fit person to be sent to the Asylum for Women at Fitchburg, Mass., and I respectfully recommend it. She is evidently a woman of bad character, and her children injured rather than benefited from her presence." The prison in Fitchburg, Massachusetts was where female southerners, suspected of being spies or providing aid and comfort to Confederates, were imprisoned.

What happened to Sarah after Turner ordered her arrest can best be told in her own words. Below is a letter she wrote to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton from Fitchburg in August 1864, followed by my transcription.

|

| (Fold3.com) |

|

| (Fold3.com) |

"Fitchburg Prison

Aug't 2nd 1864

E.M. Stanton

Sec'y of War

Sir.

I write to you hoping, and wishing when you know my case and present situation that you will give me the justice that I merit and ought to receive at the hands of every just man. I am a widow and lived in Stafford Co. Va. I am a true and loyal woman, having taken the oath of allegiance to the United States. On the 18th of last March, when in my own house, it was entered by members of the 4th Penn. and 10th New York Cavalry who were under the influence of liquor. I was ordered to leave with my old mother, and four little children, one of them at the breast. They then burned my house to the ground, not allowing them or me a change of clothing. In this condition I was taken from them, and only my God knows where they are at this time, for I have not heard a word from them since I parted from them by the burning light of my house. I was then taken to Warrenton, then to Culpeper C.H. from there to Washington City where I remained 11 days, without a trial or any hearing. I was brought to this place Fitchburg Mass on the 23rd of April. The charges brought against me by the drunken arresters, were that I had entertained Rebels, which is as false as midnight darkness. I had taken the oath of allegiance to the U.S. Government and I call my living God to hear me out that I had been true to my faith. I had nursed soldiers in my house, but they were from Company A Penn one man that I attended named John Carpenter could testify to my faith. I was engaged to be married to a man in the 8th Penn. had he not poor fellow been killed by the Rebels, could also speak in my behalf. When I was brought to this place I was led to believe that my confinement would be of short duration, but it is now three months and I have heard nothing of my release, my heart is sick of hope deferred. I hope you will do something for me that might speedily allow me to assure you again that I am innocent of the charge as an angel in heaven. Please let me hear from you.

Yours respectfully

Mrs. Sarah E. Monroe

E.M. Stanton

Sec'y of War"

|

| Velorous Taft (Courtesy of K. Kilbourne) |

During her long stay at Fitchburg Prison, Sarah had made a favorable impression on Velorous Taft, Chairman of the County Commissioners and Inspector of Prisons of Worcester County, Massachusetts. On December 30, 1864 Taft wrote to Secretary Stanton, informing him that "she has conducted herself with great propriety since her imprisonment, and has from first to last declared herself a Union woman, having no sympathy for the Rebels; that of all secession prisoners sent to Fitchburg she is the only one who has so declared, and the only one who has behaved decently...and she should be discharged." In his letter to Secretary Stanton dated January 11, 1865, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt stated: "In view of the slight and unsatisfactory evidence of her guilt possessed by the government, of her constant and continued professions of her loyalty, and her good behavior during her imprisonment, it is recommended that such clemency be extended as the Secretary of War may deem consistent with the public interest."

|

| Joseph Holt (Wikimedia) |

On January 26, 1865 the Adjutant General's Office of the War Department directed the Superintendent of Fitchburg Prison to release Sarah Monroe. On February 9 she was provided with "transportation and subsistence" so that she could return to a home that had been needlessly reduced to a heap of ashes. Sarah survived her 11-month ordeal to return home to Stafford, where she lived until her death in 1904.