For a number of reasons, not the least of which were the oppressive policies of absentee British landlords, the potato became the main source of sustenance for the rural poor in Ireland by the 1800s. When Ireland's potato crop was blighted by the Phytophthoria infestans mold in 1845, the effect on the country's people was immediate and devastating. During the next ten years, more than one million Irish starved to death, and another two million left Ireland. The engraving of the effects of the famine in Skibbeeren shown above was made by Irish artist James Mahony in 1847.

Among those who emigrated from Ireland during this period were the McCracken family, who found their way to Spotsylvania County by the 1850s. Thomas and Emma McCracken and their four sons--Patrick, Michael, Bernard ("Barney") and Terence prospered in their adopted country and contributed a great deal the civic and economic life of Spotsylvania and Fredericksburg. Their lives would be noted for both episodes of sublime grace and madness.

Bernard McCracken, more commonly known as Barney, was born in Ireland in 1836. At the beginning of the Civil War, some say he briefly served the Confederacy in Captain Thornton's Company of Irish Volunteers, which became part of the 19th Battalion of Virginia Heavy Artillery. But by 1863 Barney was working in a liquor shop in Washington, D.C. when he registered for the draft, as seen in the image below. Whether he ever wore a Union uniform is not known, but is doubtful as his name appears in the 1864 edition of the city directory as a "saloon keeper."

Soon after the Civil War, Barney married Mary F. Bowling and settled in Louisa County, where they had three children together. Barney became active in Republican Party politics and for a time served as tax assessor for Louisa and Orange counties. In 1869, he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates. The one term he served in that august body was notable for the press coverage devoted to his escapades on the floor of the House. The two articles below--the first from The Daily Dispatch of April 13, 1870 and the second from The Daily State Journal dated March 16, 1871--are examples of a colorful personality, or one that is slightly unhinged:

Thirty-five-year-old Bernard McCracken died in Fredericksburg on December 17, 1871. He is buried in the Confederate Cemetery there.

In 1856, Barney's father Thomas bought a 325-acre farm in western Spotsylvania County near Parker's Store, and divided it between himself and his sons Patrick and Michael. Where his youngest son Terence was at that time is not known; he may have been attending school somewhere. In the 1863 map detail of western Spotsylvania, the McCrackens' farm can be seen in the lower left of the image as "McCrackings."

Patrick McCracken was born in Ireland on December 4, 1826. He married Elizabeth Dickey of Orange County on March 2, 1857 and they made their home at Patrick's farm.They had one son, William, who died young.

In April 1862, troops of the United States army crossed the Rappahannock River and occupied Fredericksburg, where they remained until August. Some time in July Patrick McCracken drove a wagon load of produce into Fredericksburg to sell. His presence aroused the suspicion of overly vigilant soldiers, who arrested him and sent him to Washington, D.C. where he languished in the Old Capitol Prison for nine weeks. Patrick finally was admitted to the office of General James S. Wadsworth, who was at the time military governor of the Washington district. Wadsworth quickly decided that there was no legal basis to detain him and freed Patrick after he pledged to not support the Confederacy.

The lives of General Wadsworth and Patrick McCracken were fated to intersect one more time two years later, during the Battle of the Wilderness. On May 6, 1864 Wadsworth was leading his men in the chaotic fighting near the intersection of Brock and Plank roads when he was shot in the back of his head. While his wound was mortal, death was not instantaneous. He was taken to a Confederate field hospital set up on the Pulliam farm. Below is a photograph taken in 1866, showing the place were General Wadsworth was wounded:

News of Wadsworth's wounding and his presence at the temporary hospital at the Pulliam farm reached Patrick McCracken. Patrick packed up some food and took a bucket of milk with to go to Wadsworth and do what he could for him. Once he got there, he learned from Dr. Zabdiel Adams, who was also a wounded prisoner who had tried to help Wadsworth, that the General was unconscious and unable to eat or drink. Patrick said that the doctor could have the milk and food instead. The next day, Patrick returned to the Pulliam farm with some sweet milk, which he used to moisten Wadsworth's lips.

Wadsworth died the following day. When Patrick showed up to care for Wadsworth, he learned that he had died and had been laid aside for burial. Patrick had the General's body transported to his farm, where he made a coffin out of some doors and boards that he painted black. Patrick dug a grave in his family's cemetery and placed Wadsworth in it and covered the coffin with a plank and then dirt. He then fashioned a grave marker and placed it at the head of the grave.

Several days later, Union General George Meade sent a letter to General Robert E. Lee, seeking to make arrangements to retrieve the body of General Wadsworth. On May 12, under a flag of truce, Union soldiers came to the farm of William A. Stephens and learned from the Confederates where the General's body had been taken. An ambulance was dispatched to the McCracken farm, and the mortal remains of James S. Wadsworth began their long journey to his home town in New York.

The day after Wadsworth died, Patrick wrote this letter to his widow, which was printed in the 1865 edition of the New York State Agricultural Society:

Mrs. Wadsworth sent a sum of money to Patrick as a token of her appreciation for his kindness. According to McCracken family lore, Patrick and his brother Terence used that money to start their grocery business in Fredericksburg.

Within two months of the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox, Patrick opened a grocery store in Fredericksburg on what is now known as William Street. From the June 24, 1865 edition of The Fredericksburg Ledger:

Not long after, Patrick's brother Terence joined him as a partner in the business. After Patrick's death, Terence would have at least one other partner, but he never changed the name of the business.

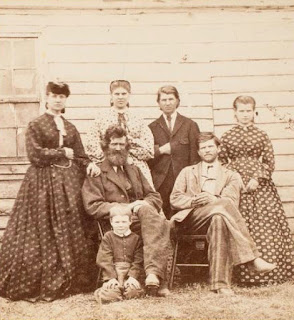

By 1870, Patrick and Elizabeth were living in Fredericksburg. The 1870 census tells us that also living in the McCracken household was Patrick's clerk, 27-year-old George Edward Chancellor. The son of Reverend Melzi Sanford Chancellor, George was a veteran of the 9th Virginia Cavalry. Within a couple of years, George opened his own store at the corner of William and Charles streets (this building still exists and serves as home to Castiglia's Italian Restaurant). Shown below is an 1866 photograph of George Chancellor (seated, wearing striped pants) with his family.

Elizabeth Dickey McCracken died on October 21, 1873. Patrick followed her to the grave on June 18, 1875. They are both buried in the Confederate Cemetery in Fredericksburg.

Like his brother Patrick, Michael McCracken also began his adult life as a farmer and slave owner in Spotsylvania near his parents. Also like his older brother, Michael married a woman from Orange County, Martha Jane Almond. They exchanged vows in Orange on December 23, 1856. They had two sons--Melvin, born in 1861 and Thomas, born in 1864.

Michael enlisted in Company E of the 9th Virginia Cavalry on April 5, 1862. By September he was detailed as an ambulance driver. He remained at this duty until he was dropped from the rolls on June 1, 1863, when he was awarded a mail contract.

Michael and his family remained on his farm until after the 1870 census. By 1873, the McCrackens had moved to Fredericksburg, where Michael started out as a saloon keeper. A few years later he and Martha built a hotel on Commerce (modern William) Street. There was also a McCracken Spoke Factory in Fredericksburg, but to which brother or brothers this enterprise belonged is not known. Michael became active in the civic affairs of Fredericksburg. He was a member of the fire department, an officer in the Building and Loan Association, a member of the Rappahannock Boat Club, and he served as town magistrate.

By the mid-1880s, the behavior of Michael's son Thomas was already making the news, but not in a positive way. From the December 11, 1885 edition of The Free Lance:

Martha Almond McCracken died on August 17, 1887. She lies buried in the Confederate Cemetery in Fredericksburg. From The Free Lance:

Four years later, the McCracken family's name would again appear in the newspapers in a highly unfortunate, indeed tragic, event. On February 20, 1891, Thomas McCracken murdered his father on William Street. The particulars were described in February 22 edition of The Richmond Dispatch:

In the ensuing trial, Thomas was found not guilty by the jury by reason of insanity. He was committed to the Eastern State Hospital in Williamsburg. He was furloughed for a few days the following year to visit his family at Christmas. From The Free Lance dated December 30, 1892:

Thomas was released from the asylum in 1902. The 1910 census shows that he was single and working as a house dealer in Bruton, Virginia. In 1920, Thomas McCracken, employed as secretary-treasurer of a syrup company, was living in Richmond with his wife and children. By 1930 he was living alone in Williamsburg and working as a house painter. After that, I find no mention of him in the public record.

The youngest of the McCracken brothers, Terence, was born in Ireland on June 21, 1844. He married Margaret Scott on December 26, 1866. By 1876, Margaret and both of their children had died. The following June he married Frances Catherine Doherty at St. Peter's Catholic Cathedral in Richmond. They had two sons, both of whom survived to adulthood.

In addition to owning the grocery and dry goods store with his brother Patrick, Terence was a member of the Building Association, the fire department, the grain exchange and the Chamber of Commerce. Beginning in the 1880s he served on the board of directors of the Eastern State Hospital, where his nephew Thomas would be committed in 1891.

Terence spent the last weeks of his life as a patient at the Laurel Sanitarium in Laurel Maryland, which treated mental illness and alcoholism. He died there on June 21, 1918. He is buried in the Confederate Cemetery in Fredericksburg. From his memorial on Findagrave:

My source for the story of Patrick McCracken and James S. Wadsworth is The Ultimate Price at the Battle of the Wilderness