|

| John Day Andrews (Ancestry.com) |

During the waning years of the eighteenth century, four sons were born in Spotsylvania County to John Andrews and Elizabeth Lipscomb. Lewis, the oldest (1793-1858), became a successful farmer in Orange County, where he and his wife raised their family. Samuel (1794-1871) never married, but achieved noteworthy success as a man of business. In 1826, he built a fine brick house in southern Spotsylvania County, at the spot that would become known as Andrews Tavern. In 1836, he added the wood-framed wing that housed the tavern. This addition was also utilized as a store, post office, polling location and a place where the local militia would muster. Living in the brick house with Samuel was his brother William (1800-1861), with his wife and six children. William ran the farming operations at Andrews Tavern, and was one of the largest owner of slaves in Spotsylvania.

|

| Andrews Tavern (Virginia Department of Historic Resources) |

The fourth son, John Day Andrews (1795-1882), achieved a well-earned place in history by the force of his will, his ambition, personal energy and his intelligence. Little is known of John's very early years, but it is clear from his letters and legal depositions that he had benefited from a first-class education. As a young man, John had an association with a young woman named Mary Goodwin. Arising from that association was a closely-kept secret that John never shared with his family. The details of that secret were revealed in two letters John wrote in 1871 and 1872. These two letters are part of a large cache of documents that once belonged to the Andrews and Johnson families, which are now in my possession. The significance of these letters will be more fully developed later in this biography.

|

| Hanover Tavern (Google) |

William Winston Thilman (1798-1829) was a member of one of Hanover County's leading families. He owned Hanover Tavern, which still stands on modern Route 301 opposite the venerable Hanover Courthouse. The tavern had been previously owned by William's grandfather during the American Revolution, and then by his father. On February 17, 1822, he married a cousin, Eugenia Price (1805-1873). Eugenia was a daughter of wealthy Thomas Randolph Price, Jr., and Elizabeth Thilman Doswell. William and Eugenia had two daughters together: Barbara Overton (1823-1857) and Elizabeth (1825-1876).

|

| Eugenia Price Thilman Andrews (Ancestry.com) |

John Andrews worked as the overseer for Eugenia Price Thilman. It is also quite possible that he had been employed as overseer before William Thilman's death. In any event, he was employed by Eugenia when they announced their plans to marry in 1830.

|

| Marriage license of John Andrews and Eugenia Thilman (Library of Virginia) |

|

| Fork Church, Hanover County (photo by R.W. Dawson) |

John and Eugenia were married by Reverend John Cooke at historic Fork Church in Hanover County on December 1, 1830. At least one source says that John and Eugenia's marriage "scandalized plantation society" in Hanover County. And that is quite possible. It has also been suggested that Eugenia's family was strongly opposed to the marriage. However, that may not be entirely true. In a letter written by Eugenia's father to John, which was entered as evidence in a lawsuit brought against him by the executors of Price's estate, Thomas Price, Jr., wrote: "...your saying you did not wish to marry in my family, unless you were considered a member. I told you as far as I was concerned I was satisfied."

However, there is no question that the relationship between Thomas Price, Jr., and John Andrews became toxic soon after the wedding, and remained so for the rest of Price's life. According to testimony given at the lawsuit mentioned above, including John's own deposition, the falling out between John and Price occurred after John's refusal to participate in a financing scheme accepted by Price's other children. Price wished to place in the possession of his children (including John and Eugenia) a certain number of slaves, each of whom was given a valuation. These slaves would be utilized for their labor while in the possession of Price's children, although ownership would be retained by Price. John refused, stating in his deposition that this would place him in the position of caring for slaves, which were not his property, at great expense "liable to be taken from him when most valuable, and in the meantime subject to the divided authority of two masters. This he refused, considering such an advancement as a Burden and not a benefit. The said Price took umbrage at his refusal."

This refusal would cost John Andrews dearly. The year before this controversy arose, in 1831, John bought Hanover Tavern at auction. This he did at the urging of his father-in-law, who--according to John--had promised to assist him in making the payments on the purchase. After this spat regarding the slaves, Price apparently reneged on this commitment, and John was left in the uncomfortable position of making good on his bond for the tavern purchase from his own resources.

|

| Thomas Price, Jr., bond to Eugenia (Library of Virginia) |

In March 1832, Price signed the document above, pledging to to Eugenia a substantial sum of money for the support of herself and her two daughters, Barbara and Elizabeth. This was likely the last financial help he ever extended to Eugenia.

By 1834, relations between John and Price had permanently soured. John indicated as much in a letter he wrote to his father-in-law on December 5 in that year: "It is I must confess truly distressing to me to find that there exists with you a want of confidence in my prudence and discretion in the application and use of any matter of property that you might find yourself enabled towards aiding in comfort to myself & those members of your family with whom I find myself honorably associated." For the rest of his life, Price refused to assist John with any financial help, or if he did so, it was done grudgingly and with strings attached. In response, John nurtured a smoldering resentment against his father-in-law.

In 1835, the first of John and Eugenia's two daughters, Samuella, was born. Her half-sisters, Barbara and Elizabeth, had been adopted (in spirit, if not by court decree) by John, who cherished William Thilman's daughters as if they were his own.

|

Richmond Enquirer 2 October 1835 (Chronicling America)

|

Despite the ongoing strife between John and Price, newspaper accounts showed that this was not the entirety of John's experience in Hanover County. In the autumn of 1835, John hosted a multi-day horse racing event. As the proprietor of Hanover Tavern, he advertised that he would "do what he can for the comfort and accommodation of his guests. Sportsmen and others are invited to attend."

John was also active in Democratic politics. In the November 1, 1836 edition of the

Richmond Enquirer, John's name appears on a list of members of the committee of correspondence from Hanover County who supported the candidacy of Martin Van Buren.

It was evidently during this time that John had made up his mind to move to Texas. He made his first trip to the Houston area in 1836. By the time he made his second trip there in 1837, he had joined forces with Baltimore merchants Thomas Massey League and Peter Wilson. Their business venture was named League, Andrews and Company. The plan was for John and League to settle in Houston, where they would establish a mercantile business. Peter Wilson would remain in Baltimore, where he ran the "front office" of the company. It was his responsibility to purchase goods for the proposed store in Houston and arrange for that merchandise to be shipped there.

These two trips to Texas required long separations from his family. As might be expected, Thomas Price, Jr., was very much opposed to the idea of his daughter and grandchildren moving so far away. There was even grumbling among some about John's "abandoning" his family during these long absences, and Price expressed doubts about John's "conjugal fidelity."

|

| Petition of Thomas League regarding the Correo (Ancestry.com) |

About the time that John returned to Hanover County in January 1838, League Andrews and Company encountered its first setback (which, though costly, was not fatal to the company's fortunes). During the summer of 1837, the Mexican schooner

Correo was captured by two schooners of the Texas Republic,

Invincible and

Brutus. The

Correo was brought to Galveston where it was offered for sale by Thomas F. McKinney, prize agent. League, Andrews and Company bought the schooner, presumably to transport goods to their store. In December 1837 or January 1838, William M. Shepherd, Secretary of the Navy of the Texas Republic, seized the

Correo and impressed her into the service of the Texas Navy. In 1843, Thomas League petitioned the Congress of Texas to recover financial damages due to the loss of the ship. Ultimately, Texas decided that it did owe League, Andrew and Company (which by then had dissolved its business) for its loss. However, it was determined that League, Andrews was indebted to Texas for a substantial amount of money, and the two competing claims offset each other.

|

| Resolution of Texas Congress concerning the Correo |

The year 1838 would prove to be pivotal for John Andrews in other respects as well. Having completed his business in Houston for now, John sailed back to Baltimore in January, then returned home. Soon after his arrival, he met with Price at his home. They agreed to meet at Bell Tavern in Richmond on January 28 with the purpose of settling some matters of business and, as Price was later quoted as saying, "to bury the tomahawk" and hopefully come to a new understanding. Shortly after this meeting, John traveled to Baltimore to meet with Thomas League and Peter Wilson, where the final touches were put on their partnership agreement. Soon after his return to Hanover County, John wrote a letter to Price on March 3:

"Dear Sir, I hasten to advise you of my return from Baltimore, and the result of my expedition. Mr. Wilson the Gentleman residing in Baltimore to whom I was proposed a partner has agreed by the advice of several friends to take me in as a partner in the Houston Concern. And I have succeeded in making a new arrangement with him much more favourable to my interest than heretofore proposed [here John goes into some detail about the financing of this venture]...I have taken much pains to investigate his circumstances and found them good, & that he is a man of good business habits. Now sir, I submit to you to say whether you do not think this is an excellent prospect for doing something to benefit my dear little family?...Now, my dear sir, if there is friendship or confidence in your bosom towards me, or if you wish to see me, or mine advanced in the scale of Human comfort or Human association, then let me beg that you now come out with a father's kindness, and a father's affection which I hope by frugality industry and prudence, will result in giving comfort to me and mine...I therefore again supplicate your speedy aid--and trust that it may be offered and extended upon principles of confidence and liberality..."

But a liberal donation by Thomas Price, Jr., would not be forthcoming, and his relationship with John Andrews resumed its longstanding rancorous and bitter character.

|

| John's letter to Price, 12 August 1838 (Library of Virginia) |

The last known letter written by John Andrews to his father-in-law was dated August 12, 1838. Remarks such as these doubtless did little to restore feelings of comity between the two men:

"...I can only say that if our intercourse has degenerated into acts of offensive insult, the sooner it receives its final termination the better...I had hoped that the expressions that fell from your lips with regard to myself, since my return from abroad, & from the many declarations of favouritism expressed by you in my hearing, in behalf of your daughter, and her little family, that a better state of feeling, and a more noble and endearing intercourse between families, was desired and sought after than had hitherto existed. But alas a silent and patient observance of passing events have convinced me that my hopes have been utterly fallacious..."

Of course, Thomas Price, Jr., had his own opinions, which he angrily expressed in an undated letter to John presented as evidence in a lawsuit instituted against John by the executors of his estate in 1839:

"What benefit do you think could or has resulted to you, for slandering me in the way you have, to various persons; if I were ever guilty of such charges, do you think those to whom you have made your communications would think as well of you. You have mistaken your man, if you think of playing off your artifice on me by your slanderous tongue & am sorry to perceive that Eugenia has imbibed many of your principles...Your saying in my house, before my wife, that my not giving you what I gave, absolutely [to my other children], would be the means of separation between you & Eugenia, and threats repeated at the Ct. House that you would send her and children to me. Your dandling and kissing that black child..."

All of this internecine squabbling would soon be overtaken by events, as the day was fast approaching when John Andrews and his family would soon leave Hanover County for Baltimore, and from there to Houston. One vital detail for which John sought reassurance was the legality of his importation of slaves from Virginia to the Republic of Texas. To that end, he wrote a letter dated October 20, 1838, to Dr. Anson Jones, who was then serving as Texas's ambassador to the United States (six years later, Jones was elected as the fourth, and final, President of Texas):

"I feel satisfied of the fact...that very many slaves are constantly being carried into Texas, but whether in a rather smuggled character or openly I am yet unadvised. I rather suspect under the former character. This by all means I wish to avoid, as I hope to be extensively engaged in commerce between the two countries and would be utterly unwilling to do anything that should be in any way subversive of what the Governments of the U.S. & that of other Governments abroad might regard as conducive to the general good among nations..."

|

| From the letter of John Andrews to Dr. Anson Jones (Texas Legation Papers) |

Another bit of business which had to be taken care of was the sale of Hanover Tavern. John began advertising his property in the

Richmond Enquirer as early as February 1838. A buyer would ultimately be found, but only just in time.

|

Richmond Enquirer, 22 February 1838 (Chronicling America)

|

About the time that John wrote his letter to Dr. Anson Jones, a totally unexpected accident occurred which put increased pressure on John to get his affairs in order so that he could leave for Texas by the end of 1838. Thomas Price, Jr., suffered "a violent injury of the spine, which produced compression of the spinal marrow." For the last two weeks of his life he lay paralyzed in his bed. He was visited by many persons during his final illness, including John Day Andrews. Charles Dabney testified at a hearing during the lawsuit against John that Price asked John not to move to Texas, & that if he stayed in Virginia he would give him "Rocketts" and other property in Hanover County. Price died on October 31, 1838.

|

| From the will of Thomas Price, Jr. (Library of Virginia) |

Price had written his last will and testament on October 31, 1837. Not surprisingly, his will did not mention John or his daughter Samuella. The will did not even mention mention Eugenia by name. He did refer to her, however, in his bequest to the daughters of William Thilman:

"One other portion I give and bequeath to my Grand daughters Barbara O. and Elizabeth Thilman. But on the express condition nevertheless that if any time that their mother should be in a state of poverty and destitution, they shall pay to her in equal portions the annual sum of one hundred and fifty Dollars, during the said necessity. And if they or either of them shall fail to do so then their or her said portion to be entirely forfeited..."

John sold Hanover Tavern and about 600 acres to Francis Nelson of King William County on December 8, 1838. The purchase price was $8,000. Six thousand dollars of that amount was to be loaned to Nelson by Price's son, Dr. Lucien B. Price. Most of the remaining $2,000 was to come from the estate of Thomas Price, Jr., by way of a somewhat convoluted arrangement. John held his bond for $1,591 due to Price, who had signed a release indicating that the debt was satisfied. That credit was to be applied to the tavern purchase. Soon after John and his family moved to Texas, Dr. Lucien B. Price and Benjamin Pollard, Jr., the executors of Price's estate, sued John in Hanover County Circuit Court, alleging that John had forged Price's signature on the release. The case file for this lawsuit, amounting to almost 300 pages of depositions, interrogatories and other evidence, dragged on in various courts from 1839 to 1871. The case was ultimately dismissed.

John, Eugenia, Samuella, Barbara and Elizabeth left Hanover County about December 20, 1838. They traveled to Baltimore, where they boarded a ship loaded with building materials for their new house in Houston, as well as goods for the store owned by League, Andrews and Company. Their new life in Texas would begin in early 1839.

|

| Telegraph and Texas Register 28 November 1838 |

John Andrews built a two-story house at 410 Austin Street in Houston. This has been credited as being the first multi-family house in Houston, as Thomas League and his family occupied the top floor for a few years. John and League ran a store in the Houston House at the corner of Main and Franklin streets until their partnership dissolved in the early 1840's.

|

| Invoice of League, Andrews and Company |

|

Morning Star [Houston] 9 January 1840

|

Almost from the day he arrived in Houston, John Day Andrews began to make significant contributions to the civic and economic life of the city. His impressive list of accomplishments was neatly summarized in an article written by Priscilla Myers Benham for the Texas State Historical Association:

- In 1841, he was named superintendent for the newly-chartered Houston Turnpike Company, whose purpose was to build a road between Houston and Austin.

- John and Eugenia were charter members of Christ Church, established in 1839, which remains the oldest existing congregation in Houston.

- He helped organize and became the president of the Buffalo Bayou Company, which was charged with the responsibility of removing obstructions in the bayou in order to facilitate shipping traffic between Houston and Harrisburg.

- In 1839, League, Andrews and Company was among the $100 contributors for the purchase of an engine house for the volunteer fire company.

- He served as president of the board of health, established in 1840.

- He served two terms as Houston's fifth mayor, 1841-1842.

- He helped to establish the Port of Houston Authority.

- He was largely responsible for building Houston's city hall, completed in 1842.

- He was asked by Sam Houston to become secretary of the treasury for the Republic of Texas, an honor he declined.

- He was the first president of the first school board of Houston City Schools.

- Andrews Street in Houston is named in his honor.

John and Eugenia's second daughter, Eugenia, was born in Houston on November 15, 1840. At some point in time, Eugenia's oldest daughter by William Thilman, Barbara, returned to Virginia. She married Robert Taylor of Culpeper County, where she died on May 1, 1857. Her sister Elizabeth married Daniel D. Culp in 1844. After his death in 1852, she married Scottish immigrant John Dickinson. Elizabeth died on on February 29, 1876 and is buried in Glenwood Cemetery in Houston.

Samuella Andrews married James Kemp Holland on March 22, 1854. Holland was a successful planter who served several terms in the Texas House of Representatives. During the Civil War, he served as aide-de-camp to Governor Pendleton Murrah. On October 2, 1865, two of the Hollands' children, John Day Andrews and Nannie Hicks, died within hours of each other of "congestion." Three days later, Samuella died after having suffered from gastroenteritis for 41 days.

Samuella's sister, Eugenia, married Dr. Robert Turner Flewellen on April 25, 1860. In addition to his medical practice, Dr. Flewellen served several terms in the Texas House of Representatives. In 1872, he was elected President of the Texas state medical association. In 1878, he introduced a bill in the legislature that chartered a medical college in Texas. Eugenia Andrews Flewellen lived until May 17, 1923. She is buried in Glenwood Cemetery in Houston.

Soon after his arrival in Texas, John began to buy farm land, and over the years became a successful planter and substantial landowner. By 1870, his real estate holdings were worth $100,000. His younger brother William, who owned dozens of slaves in Spotsylvania at Andrews Tavern, also invested in Texas real estate and was an owner of slaves in that state as well.

John's older brother, Samuel, represented his legal and financial interests during his absence from Virginia. In August 1861, with the Civil War already well under way, Samuel wrote an advertisement for his brother, in which he made known John's desire to have additional slaves brought to Texas from Virginia:

The issue of secession was put to the voters in 1861. John described his point of view at that time in his application for a presidential pardon in October 1865:

"When the question of secession of Texas from the American Union was presented to the citizens of this state, he quietly voted for secession, honestly entertaining the political opinion that a state, in her sovereign capacity, might withdraw from the Union, without an infraction of the Constitution of the U.S. States." John went on to state that much of his accumulated wealth "has been swept away by operation of the Emancipation Proclamation." John then reassured President Johnson that he "has not engaged in outrages or wrongs upon any citizen because of his Union sentiments. That he has belonged to no Vigilance Committee or secret organization for the prosecution of Union men, that he has in his hands no property belonging to the United States or the late so-called Confederate States."

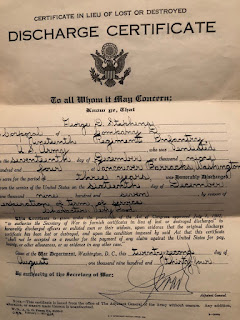

|

| Amnesty Oath of John Day Andrews (Fold3.com) |

In the second paragraph of today's post I referred to a little known chapter in the life of John Day Andrews. John himself revealed this secret in two letters written to Joseph Henry Johnson of Orange County, Virginia. Johnson was the son-in-law of John's brother William, and he was also the executor of William's estate (William died in 1861) and he had been William's attorney-in-fact in matters relating to his Texas investments.

|

| From John Andrew's letter to Joseph H. Johnson, 1871 |

|

| From John Andrew's letter to Joseph H. Johnson, 1872 |

In his first letter to Johnson (which is undated, but by context is known to have been written in 1871), John wrote:

"We rarely hear from you or our other friends in Va. Let me know how my Tinder connections are getting on try & find out if the boy William Tinder is at all promising also Mr. Pendleton and his son. Samuella Tinder I know is smart--how I would if alone like them all near me but Mr. Johnson my wife and daughters do not know of these dependents of mine, & I don't wish to distress them by placing them here. If they could & would act smart & say nothing of me & their connection with me I could materially aid them if out here--if you ever see Samuella Tinder & her brother Wm Tinder I authorize you to name these things to them & to know if they can keep this as one of their own secrets.

"I shall expect you if you can to place or hand this money [illegible] to Samuella & her brother Wm &c & write to me. I am 76 years old now, Can't hope to live long. Yours most truly

J.D. Andrews"

So who were Samuella and William Tinder, and what was their connection to John Andrews?

They were his grandchildren.

Samuella (1841-1887) and William (born 1849) were the surviving children of Spotsylvania residents John A. Tinder and Sarah F. Goodwin (1814-1849). Sarah Goodwin was the illegitimate daughter of Mary Goodwin and John Andrews. In the abstracts of the Spotsylvania Circuit Court, Sarah F. Goodwin is identified as the "bastard daughter of Mary Goodwin." John Andrews is listed as one of the defendants in a lawsuit brought by James L. Goodwin.

|

| From the abstracts of the Spotsylvania Circuit Court |

The "Mr. Pendleton" mentioned in John's 1871 letter was Robert Lewis Pendleton, who had been the husband of Samuella's sister Laura, who died in 1869. Robert married Samuella in 1873.

Like his father-in-law William Andrews, Joseph Henry Johnson owned real estate in Texas, specifically, a city block in Houston. During the chaos of the Civil War years, the taxes went unpaid on the property of both the late William Andrews and Johnson. In the years following the war, John Andrews paid these taxes. In his second letter to Johnson, dated March 12, 1872, John asked Johnson to apply that credit to a payment to be made to Samuella Tinder:

"I hope you will turn the amount over to my relative Samuella Tinder & for the little boy of Laura Pendleton Dec'd. Miss Samuella Tinder's receipt may be taken for the whole amount with instructions to help the others as when may seems best--and her receipt send to me."

|

| Receipt of Samuella Tinder |

John also mentions in each of these letters the state of his health and that of his wife, Eugenia. From the 1871 letter: "My health in the main is good my dear wife has been very ill in last 90 days but is now much mended is walking about again was confined to her room for 60 or 70 days--is very much reduced in flesh is almost a skeleton." And in March 1872: "Myself and wife are rapidly growing quite old. My dear wife has had a severe attack this winter & spring for full 4 or 5 months has been confined to her room. We are both up and she is traipsing our lots and yard. But she is very thin in flesh...I am nearly quite Blind, & am becoming very deaf."

Eugenia Price Thilman Andrews died July 11, 1873. She is buried in Glenwood Cemetery in Houston.

|

John Day Andrews (Courtesy of Phillip Dickinson)

|

The eyesight of John Andrews continued to fail. His daughter Eugenia Flewellen and her family moved into John's house at 410 Austin Street and cared for him during his last years. He died August 30, 1882 and is buried next to his wife in Glenwood Cemetery.

|

Galveston Daily News 30 August 1882

|

Selected Sources:

Texas State Historical Association (

Click here for link)

Hanover County Chancery Causes, Index No. 1872-016. Library of Virginia (

Click here for link)

Texas Legation Papers (

Click here for link)

Laws Passed by the Eighth Congress of the Republic of Texas. Houston: Cruger & Moore, Public Printers, 1844 (

Click here for link)

Exhibits--Hanover Tavern (

Click here for link)

"Mr. Holland of Grimes" (

Click here for link)

Daughters of the Republic of Texas, "Patriot Ancestor Album," Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing Company (

Click here for link)

Texas Memorials and Petitions 1834-1929, Ancestry.com (

Click here for link)

y

y